True Crime Series and Movies: Why Do We Like It So Much? Here Is an Explanation About This Topic

We have the impression that in the last ten years True Crime series and movie has been able to transform itself from a niche product to a real transversal genre, cinematographic and serial. We speak of an impression because, curiously, the interest aroused by the various cases of crimes that occurred is not a recent matter: pamphlets, sheets and chapbooks all centred on stories of serial murder and fraud date back as far as the sixteenth century and have proliferated over the next two centuries, in Europe as well as in the United States and Asia. In the 1920s, True Detective arrives, and in the 1960s In Cold Blood by Truman Capote. Today there is much more. The human being, perhaps, is by nature attracted to evil and villains: what else could explain the longevity of this non-fiction category of fiction, today more fruitful than ever?

True Crime Series and Movies: From Podcasts to Series

The increase in popularity of True Crime is a continuous flow, never interrupted, which has been able to transmigrate from one medium to another, changing shape in parallel with the means of communication. This is explained by Tanya Horeck, author of Justice on Demand: True Crime in the Digital Age. According to Horeck, the success of True Crime in the digital age is to be found in the very nature of the genre, based on the registration and collection of information as is the experience of search engines and social networks, often used for their ability to allow us to “find out about someone”. It is thanks to the exploit of podcasts that True Crime has found its ideal digital form, halfway between the fictional series – due to its narrative nature – and radio.

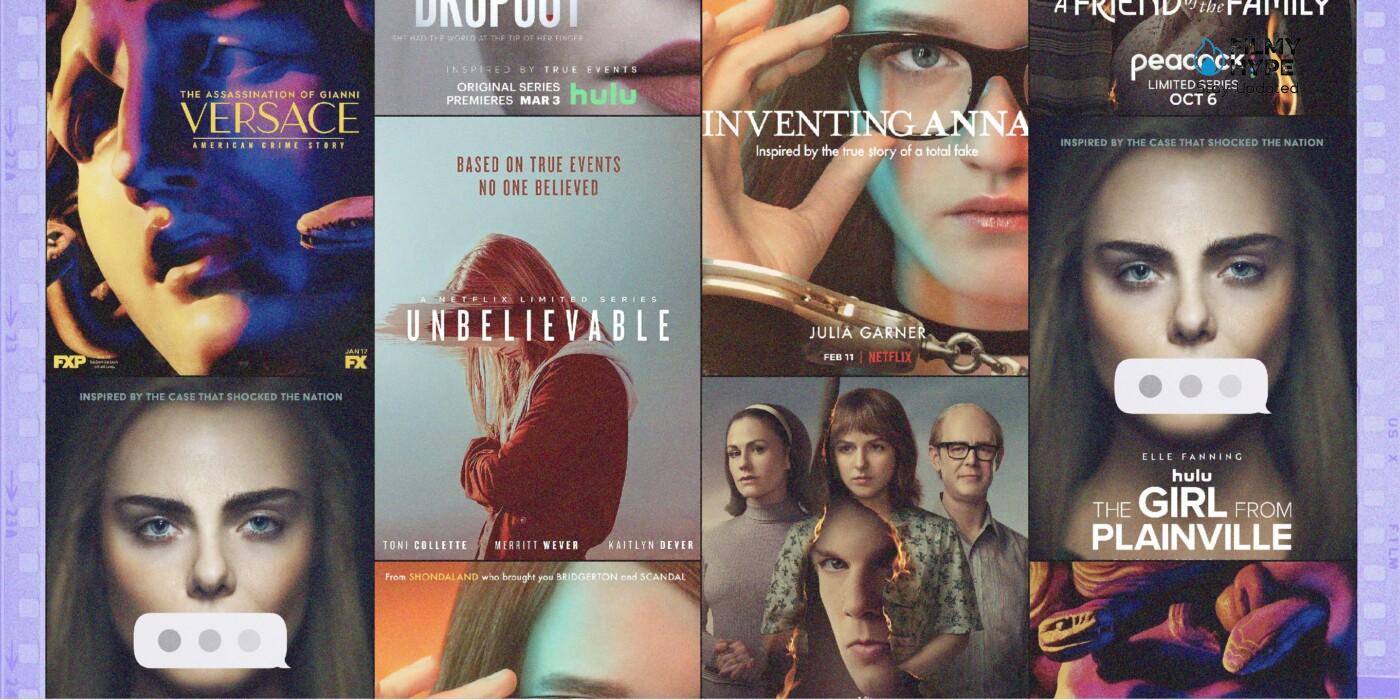

Platforms and Documentary Miniseries

A discourse on this genre, today, could not end with an analysis of the podcast phenomenon, because it should necessarily also involve a reflection on the film market and, in detail, on streaming platforms. Only on Netflix, there is an entire section dedicated to documentaries, especially in the form of miniseries, which tell of heinous crimes, whether serial or not, of blood or otherwise. Impossible not to remember Tiger King, appreciated by the public and critics, who told the story of the criminal zoo operator Joe Exotic; difficult not to mention The Night Stalker or Making a Murderer, with which for the first time Netflix has decided to publish the first episode at the same time also on YouTube, once again sealing the obliquity of true crime between platforms. Anyone wishing to enrich their culture in terms of violent crimes would find bread for their teeth, between stories of stalkers and stories of false culprits (this is the case of the beautiful The Confession Killer).

Conversations with Bundy and Dahmer

From documentaries, it was inevitable, we moved on to films and television series. Ted Bundy – Criminal fascination (Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile the original title), in which the interpretation of an unpublished and in great shape Zac Efron stands out, adapts a book in which the historical girlfriend of the murderer – here played by Lily Collins – tells his point of view. The release of the film is accompanied by Conversations with a Killer: the Bundy case, a mini doc by Joe Berlinger that draws on over 100 hours of recordings of interviews made with the killer.

Once the success of this operation has been ascertained, the platform has clear ideas on the editorial line to take. And here in 2022 Dahmer comes out, Ryan Murphy’s global success and reinforced by two conversations (one with Dahmer and the other with John W. Gacy, which peeps out in the last episode of the series). The only product that managed to unseat Dahmer in the ranking of the most clicked and viewed products was The Watcher, another true crime series by Ryan Murphy. If in the second case Murphy explores the nightmare of a family harassed by neighbors in the small and peaceful Westfield with a paranoid-Polanskian lens, in Dahmer the approach is mixed: it tells the psychology of a monster in the making, but at the same time there is a social critique of the system of institutions that have made it possible to spread its actions.

Criminal Charm?

According to an experiment conducted by two researchers from Northwestern University, people tend to favor portraits of villains because they offer the possibility to investigate their evil sides. Without these being implemented in their real life, and therefore without their outwardly reflected image being affected in any way. This would explain at a deeper level the forbidden fascination, suggested by the Italian title of Ted Bundy, on which films and TV series have long relied to win the attention of large masses of spectators. With anti-heroes that have become mythical, like Breaking Bad’s Walter White/Heisenberg or Jimmy/Saul of its spin-off prequel, the discourse becomes even more essential. Empathizing with the bad becomes easy, in this case, because the protagonists are not bad ad litteram, how much worse they eradicate the very dualism of good-evil, certainly uncomfortable and castrating for any analytical approach towards the phenomenon of identification.

An Ethical Question

It, therefore, becomes possible to explain the unanimity of applause received by Dahmer, who speculates on the attraction exerted by the monstrous figures that really existed but does so using different points of view, including that of the victims. This is because it is not possible to conceive a True Crime work, with roots embedded in stories of real executioners, deaths and pain, without first addressing the issue from an ethical and moral point of view. True Crime is the terrain in which investigation and the documentary approach meet fiction and fiction: the anti-hero is reworked by maximizing the distance between the spectator and the character, soliciting human compassion for the damage caused by a defective environmental context but denying any feeling of empathy towards the executioner.