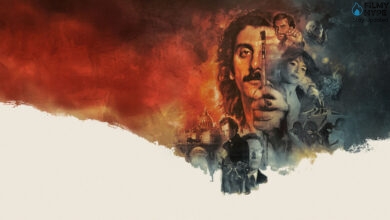

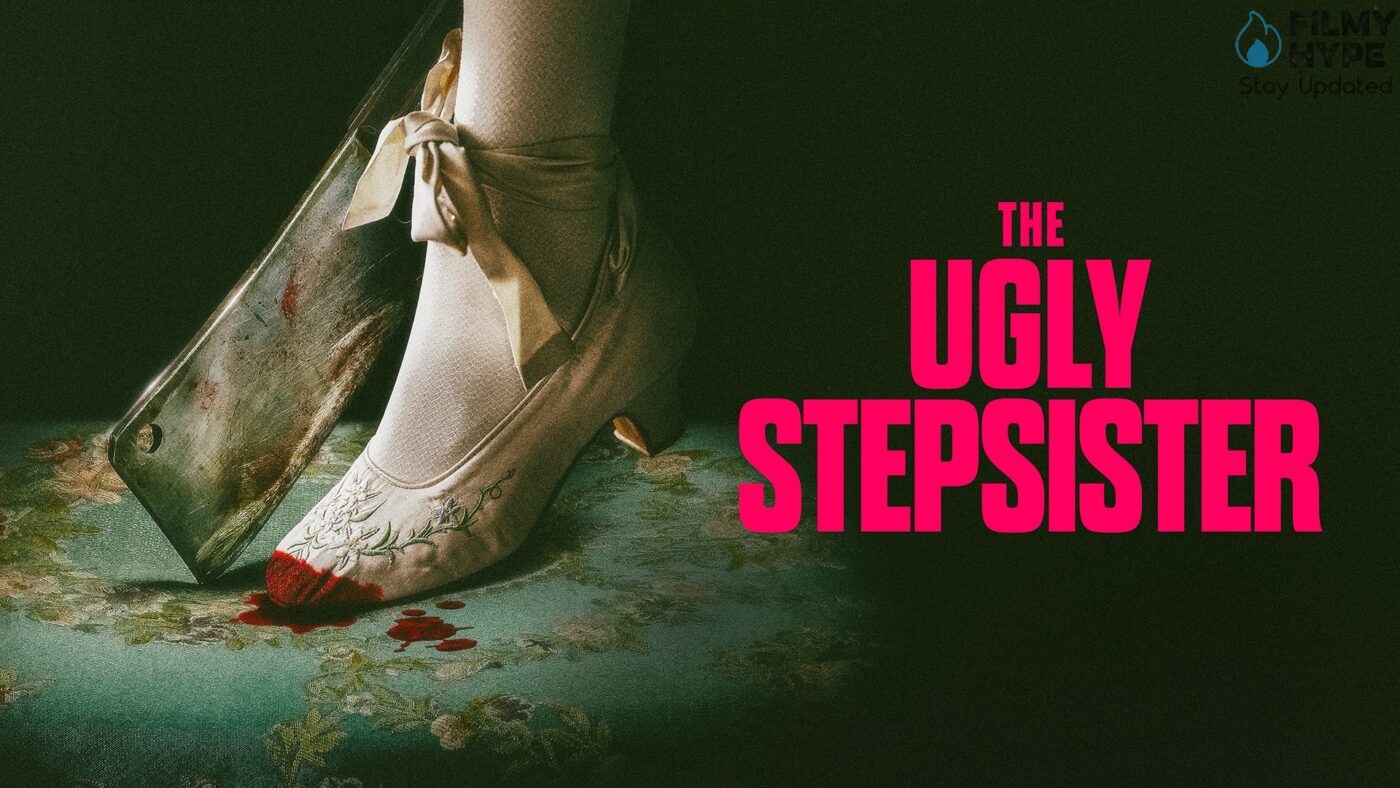

The Ugly Stepsister Movie Review: The Fairy Tale About a Sick World! (Den stygge stesøsteren)

Set in an imaginary Sweden between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, The Ugly Stepsister (Den stygge stesøsteren) by Emilie Blichfeldt – from 30 October in Italian cinemas – turn the Cinderella fairy tale upside down from the point of view of “bad”: Elvira (Lea Myren), eldest daughter of Rebekka (Ane Dahl Torp), lands with his mother and sister Alma (Flo Fagerli) in the home of a fallen nobleman. Here he lives Agnes (Thea Sofie Loch Næss), Cinderella “official”: ethereal, beautiful, ready to be exhibited in the kingdom’s marriage market. When Prince Julian (Isac Calmroth) announces a dance to choose his future wife, Elvira becomes convinced that the only way to compete is to bend your body to an ideal unattainable with perfection. The Norwegian director chooses the most uncomfortable angle: telling the story birth of the “monster” as a social product. Nothing Manichaeism’s: Agnes is not an immaculate icon, Elvira is not alone nemesis. The two embody opposing survival strategies within a patriarchal structure where marriage is money, the capital youth, beauty a weapon (or a condemnation).

The achievement of beauty and aesthetic perfection, the obsequiousness to the canons established and constructed by male society, have become a theme of reflection for horror stories, starting perhaps with the TV series Nip/Tuck, which in 2003 showed what cosmetic surgery meant in terms of violence against bodies. But upon closer inspection, the precedents are more distant and more atavistic; they are the fairy tales that have accompanied us throughout childhood, often sweetened by their horrible potential. Emilie Blichfeldt, a Norwegian director who made her feature film debut with, draws on this potential The Ugly Stepsister, presented at the Trieste Science Fiction Festival and immediately in cinemas: the film is the story of Cinderella however, seen from the eyes of her half-sister, the one who in the versions we know is ugly and bad, while here she is just ugly, at least according to what everyone tells her, starting from the mother who wants her daughter to marry the prince to revive the disastrous family finances. And he craves that marriage so much that he imposes a series of terrible tortures on his daughter to make her beautiful and desirable.

The Ugly Stepsister Movie Review: The Story Plot

Once upon a time, there was Elvira, an ambitious girl who dreamed of marrying Prince Julian. Unfortunately for her, beauty was not her virtue, and in the kingdom, the only way to win the heart of the prince was to embody an ideal of aesthetic perfection. From here begins a descent into the depths of vanity: a journey made of pain, screams, and blood. Emilie Kristine Blichfeldt‘s film may be reminiscent of The Substance, but it does a different thing. If Coralie Faregate told the parable of a star willing to do anything to stay young and desirable, in The Ugly Stepsister, the obsession becomes more physical, visceral, monstrous. Body horror is central: Elvira’s body transforms, writhes, deforms in the name of an ambition as petty as it is destructive. But at what price?

The point is that we are faced with another director – the Norwegian Emilie Kristine Blichfeldt– who chooses gore, disgust, and violence towards the body to talk about women’s eternal pursuit of an aesthetic ideal closed to them for genetic, natural, and social issues. In The Substance, it was the advance of time that put the protagonist in front of the impossible challenge of remaining equal to her young self. The challenge that Elvira faces in The Ugly Sister is, if possible, even more impossible: from the start of the film, when she sets her eyes on her half-sister Agnes, she knows that if the prince of the kingdom sees her, he will choose her in marriage. Very young and in the midst of her adolescent beauty, she is already a lost bet: too fat, too ugly, too awkward, with a slightly imperfect nose.

The fact that the protagonist Lea Myren (whose big blue eyes, wide open in amazement, horror, or pain, do half the work), neither of these things, only makes watching the film even more grotesque. This reworking of the Cinderella fairy tale is narrated from the point of view of a half-sister madly in love not with the prince, rather, of the image that the nobleman gives of himself through his pretentious, saccharine poems published throughout the kingdom. After becoming related to Agnes’ family, she finds herself having to get married to help her mother and sister with blood, but remains determined to do anything to win him over when the prince calls a ball to look for his bride.

Elvira’s true cardinal sin, for which she is punished over and over again in the film it is not the supposed ugliness, the cruelty she sometimes expresses towards her stepsister, not the ambition, but rather his is naivety. In fact, the protagonist maintains a certain purity of a girl who knows nothing about the things of the world, which Agnes/Cinderella (Thea Sofie Loch Næss) seems to already know inside out: more adult, more conventionally beautiful, but above all more cynical, pragmatic and disenchanted, she is ready to face the world in a way that Elvira is not. It is no coincidence that only one of the two already knows men biblically and knows what to expect precisely from them.

The Ugly Stepsister Movie Review and Analysis

Blichfeldt demonstrates a personal and courageous vision, but not always fully controlled. The attempt to create visceral empathy with Elvira is lost in a discontinuous narrative, which alternates moments of intense tension with long contemplative pauses. The Cronenbergian inspiration is obvious, but the film never manages to be truly disturbing: it seems to want to provoke, but it always stops one step before the trauma. Pain, rather than experienced, is aestheticized. The writing is ambitious, but often didactic. The reversal of fairy-tale roles is interesting, but it doesn’t find a real evolution. Is Elvira a victim or executioner? Is beauty tyranny or desire? The film raises important questions, but offers no answers, leaving the viewer in a suspension that is more sterile than disturbing. The open ending, which should leave you upset, turns out to be ineffective, lacking the tension that a horror film should be able to build.

Visually, The Ugly Stepsister is a kaleidoscope of quotes and contrasts. Marcel Zyskind’s photography recalls Marie Antoinette by Sofia Coppola, with its pastel colors, natural lights, and decadent dream atmospheres. But it is in Manon Rasmussen’s costumes that the film finds its most original signature: a bold mix between nineteenth-century Gothic and ’60s kitsch, with deliberately ridiculous silhouettes, shiny fabrics, lace, and grotesque details that seem to come out of a water musical. Each dress becomes a statement of intent, a visual commentary on the warping of desire and the obsession with appearance. The body, mutilated and adorned, is at the center of the scene, in a game of contrasts that amplifies the sense of discomfort. Signed by Kaada and Vilde Tuv, the soundtrack mixes ethereal harps and synthesizers with ironic pop songs, creating an alienating atmosphere that winks at Poor Creatures of Lanthimos, but without the same irreverent force. The musical commentary accompanies Elvira’s descent into madness, but fails to have as much emotional impact as it should.

Lea Myren, in the role of Elvira, is the real revelation of the film. His performance is intense, physical, courageous: he manages to embody fragility and madness with a disarming naturalness. The rest of the cast, although solid, struggles to emerge. The secondary characters remain sketchy, archetypes rather than individuals. Agnes, played by Thea Sofie Loch Næss, is a magnetic but little-explored presence, almost a shadow that looms more than a well-rounded character. The staging holds the double tension between refined and repulsive. The photography of Marcel Zyskind, who works in chiaroscuro, mottling faces with a “pictorial” light which harks back to the 19th century; the halls, the velvets, the waxy blues of the clothes make up a sumptuous tableau that the director pricks with sudden incursions into the grotesque. The costume design of Manon Rasmussen doesn’t illustrate an era only: stratify symbols – corsets as cages, wigs like masks – and makes the wardrobe a lexicon of domain.

The assembly of Olivia Neergaard-Holm keeps the film in balance: alternating the ritual (the dance rehearsals, the dressing of Agnes) with the obscene surgical, preventing the narrative from slipping into complacency. The upbringing music of Vilde Tuv and Kaada grafts a Controlled Anachrony: Electronic Inserts on Iconographies from other times that make the thesis explicit – the present resonates within the past, because the rules haven’t changed that much. Lea Myren sculpts one Elvira who doesn’t ask for forgiveness: naive and ferocious, both victim and agent of his own martyrdom. It’s his look at guiding empathy, to make us feel the price of transformation. Thea Sofie Loch Næss avoids the “sanctification” of Agnes: hers is one pragmatic clarity, the awareness that beauty can buy margins of freedom – at the cost of other constraints. Ane Dahl Torp outlines one memorable Rebekka: a mother executioner and, in turn crushed creature from the same rules he imposes on his daughter. Flo Fagerli (Alma) is the counterpoint: silent, lateral, let a possible filter through the gap of tenderness in the mechanism of violence.

In the third act, the screenplay explicitly includes some thematic lines already legible in the images: an overabundance of explanations that takes away the air from the unsaid. Some emotional junctions – in particular the relationship Elvira/Alma – would have deserved more breathing space to release everything his power. Yet the film holds up because he doesn’t look for easy morality, prefers the contradiction to the thesis, the scar on the sentence. Compared to other recent titles that intertwine fairy tales and body horror, The Ugly Stepsister convinces for cohesion and visual courage, and perhaps slightly less for the dramaturgical finesse. But when he lets the bodies speak, the fabrics, the noises of meat, reach a rare intensity. First work ambitious and personal, The Ugly Stepsister it’s a coming-of-age tale in reverse: not entry into adulthood but learning the cruelty necessary to exist in a system that monetizes desire and consumes bodies. Blichfeldt signs a debut that dirties the fairy tale with mud and blood and restores the “villains” the dignity of characters – not pawns – inside a world that demands beauty and accepts mutilations.

The Ugly Stepsister reworks the history of the fairy tale by looking at Sofia Coppola’s cult Marie Antoinette, or with a playful touch of musical and historical anachronism, mixed with an abundant dose of horror towards an ever-excessive body. There is a cosmetic surgeon who is a bit of a mad scientist and a bit of a “fairy godmother” of Elvira who tries to make her a make-over, but there are also gruesome scenes that are nothing more than the stuff of the dear old Brothers Grimm, who, in body horror they splashed around. Initially, Elvira is “only” a helpless victim of her mother’s attempt to transform her into a valuable commodity for the rich noblemen of the kingdom. For example, when he undergoes a very painful rhinoplasty, Poca doesn’t even choose the shape of the redone nose, but rather her mother.

The only awareness she acquires in the film is even more frightening: it is that of being able to choose for herself how to brown her body to become more beautiful, that is, thinner and more similar to a farcical version of Agnes, until the grand finale to actively face the most grotesque and painful transformation of his body to adapt it to proportions that are not his. Elvira’s real tragedy and her damnation is that of sees his limits clearly but not those of others. The generation this film seems to be addressing would define her “illulu” for how she meets the prince, who turns out to be a narrow-minded and despicable person, but this revelation does not change her goal one iota. Spoiled and sometimes cruel, but also alone and exploited by those who should protect her, she is moreover trapped in a sometimes delightfully ambiguous and sometimes rather confused relationship with her sister Alma (Flo Fagerli) and with Agnes. The Ugly Stepsister confronts her with the cruelest outcome: getting what she wants and finding out she was right anyway – it wasn’t enough anyway.

The movie is full of striking stylistic insights that combine a wedding favor and costume movie aesthetic with gore scenes that are truly disgusting and worthy of the body horror denomination. It also has quite a few flashes, like a certain voyeuristic streak that permeates both sisters, or pigeonholing Agnes as a person who is, all in all, a prisoner of certain classist logics, so much so that she does not rebel against her being relegated to being a servant. On the other hand, the film is all built on the combination of prostitute/virgin, princess/servant, giving the protagonists no way to think differently. It’s therefore a shame that certain ideas remain so may the final resolution of the story of Elvira and the other young protagonists come from the blue: the film writes its protagonist well, but wastes the possibility of having a trio of memorable female characters with Alma and Agnes, just as it leaves the generation of mothers and guardians who educate girls to behave like this and who react badly to their rebellion. Emilie Kristine Blichfeldt‘s priority and predilection lie in the visual dimension (i.e., the same limit found in The Substance). He willingly sacrifices the evolution of his protagonists to make it visually horrifying in a memorable scene, when it is difficult to eradicate from within oneself the desire to be different to please others.

That’s fine for an indie film which, despite doing everything trendy today in literature, at the cinema and on social media, manages to entertain and scratch. Emilie Kristine Blichfeldt is not afraid to show horror in its crudest and most disturbing form. The film spares the viewer nothing and, in the finale, recalls one of the original epilogues of the Cinderella fairy tale, but it exasperates him to the extreme. Elvira’s ambition devours her inside and out: her face is deformed, her body is sewn, cut, and reshaped like an experiment gone wrong. How far can you go to get what you want? Envy and competition become corrosive forces, and in a world where beauty is a currency of exchange, Elvira transforms into a monster of sacrifice. It even hosts an intestinal parasite to change its body. And then, of course, there is the issue of the slipper…

This is not the Cinderella we know. Yet, some trace of a fairy tale resists, like a distant echo of a now corrupt childhood dream. Elvira’s wish is simple, almost naive, but it soon turns into a nightmare from which there is no awakening. The fairy tale returns to its darkest origins: no happy endings, morally ambiguous characters, and toxic and cruel dynamics. Telling everything from Elvira’s point of view is a ploy with which the director speaks in the present tense. And who better than a woman can talk about the pressure, manipulation, and aesthetic violence of a world obsessed with beauty? The Ugly Stepsister is a black fairy tale without morals, but full of uncomfortable truths: those of a society that speculates on the pain and fragility of those who cannot conform to impossible standards.

The Ugly Stepsister Movie Review: The Last Words

Although it does not stand out for its originality due to its story being known to all, The Ugly Stepsister is a truly disturbing fairy-tale horror, with a dark style, where violence transports the viewer into a world in which love no longer has any meaning in the face of the business of beauty and perfection. The Ugly Stepsister it’s a very fascinating visual experiment, but narratively weak. Body horror is more aesthetic than disturbing; the criticism of female beauty remains on the surface, and the open ending leaves neither disturbance nor reflection. A film that wants to be subversive, but is lost among quotations, ambiguity, and an aesthetic that, while brilliant, fails to bear the weight of its ambitions. Ultimately, a shoe that doesn’t fit.

Cast: Lea Myren, Ane Dahl Torp, Thea Sofie Loch Ness

Directed: Emilie Kristine Blichfeldt

Filmyhype.com Ratings: 3.5/5 (three and a half stars)