The Boy and The Heron: The Explanation of An Ending in Which the Meaning Of Life Is Hidden

Let’s discover the explanation of the ending of The Boy and The Heron, in which the very meaning of life according to Hayao Miyazaki is hidden. Hayao Miyazaki’s works never offer a simple, pre-established, or even obvious epilogue. His stories are an emotional journey within which the conclusion arrives as the fruit of an evolution, an inner growth obtained only by letting oneself be carried away by his imagination and, above all, by that sense of magic that permeates every single image. For this reason, some endings turn out to be cryptic, especially for those who prefer the classic and always evident “happily ever after” in the Disney style.

It is not surprising, therefore, that his latest The Boy and The Heron may encounter these interpretative difficulties, especially as regards the epilogue which brings together the very meaning of life composed of the acceptance of change, of emotional loss, passing through the discovery of one’s origins. All this while always crossing a parallel world where magic is the master, spirits can become guides and, at the same time, enemies. Fundamental, however, is the path taken in this case by the young Mahito to return to life and accept his present. To understand the path constructed by Miyazaki through different symbols, let’s try to explain the ending of The Boy and The Heron in more detail.

The Boy and The Heron: The Strength of Symbolism

To understand the narrative beauty of the latest effort by the master of Japanese animation it is necessary to start from an essential assumption: every single element used and shown has a highly symbolic value. This means that everything is different from what it seems but, above all, it has the task of giving a recognizable shape to the internal problems of the young Mahito. The boy, in fact, after losing his mother in a tragic fire during the fighting in the Second World War, finds himself transported to a world that he does not know and rejects. The father started a new relationship with his wife’s sister. The similarity between the two women strikes Mahito intensely but, at the same time, distances him even more emotionally, given the loss of his mother. Added to this, then, is the strangeness of a new environment into which he has been led to distance himself from the big city while waiting for the war to end.

All disturbing elements in Mahito’s soul produce an absolute detachment from what he shows and what he feels. Thus, surrounded by a world of caring but absent adults, he finds himself having to manage alone the complicated process of mourning and the painful but inevitable acceptance of his mother’s death. A path that Miyazaki chose to represent through the construction and use of a mysterious place like a tower, inside which a parallel universe managed by magic is kept. The comparison, therefore, between the magical world and the natural world is evident. At the same time, however, another mirror relationship is also highlighted. The tower is nothing other than a symbolic representation of Mahito’s emotional torment. An inner world that hides from anyone, perhaps even from himself, in which the only reason for living is the search for his mother. For this reason, therefore, the only way to accept the actual reality is to completely immerse yourself in the emotional one, hoping to find the right motivation to return to life.

The Evolutionary Journey

When the young Mahito is pushed to enter the tower, a real evolutionary journey begins. A kind of descent into the underworld of one’s feelings which involves confronting one’s greatest fears. Spurring him towards this adventure is a heron which, taking on different forms, encourages him to attempt the undertaking, revealing to him that he can find his mother still alive. And the memory of him in Mahito’s heart and mind has certainly not faded. But for the boy, it is still too early, and his pain does not allow him to understand the many meanings hidden behind the very concept of life and survival. Crossing the entrance to the tower, therefore, he comes into contact, one step at a time, with the deepest levels of his soul, while the desperation of an “abandoned” son leads him to become his mother’s savior.

Next to him on this path is the heron which, in alternating phases, almost shows an attitude of betrayal. A necessary attitude to encourage Mahito to move forward and not retreat when faced with the most mysterious situations and emotions. But why did Miyazaki choose the heron as his totem animal? To understand it is necessary to turn to Japanese culture. This, in fact, attributes to the bird a very important meaning linked to good luck, longevity, and hope. In addition to this, the animal is also considered a national treasure. A detail that the director could have used to create another symbolism: the heron as a reflection of a country wounded by war that tries to protect its natural riches.

Embracing the Future

In this descent into the depths of emotions and the magical world that they compose, therefore, Mahito is destined to meet various creatures such as, for example, the poetic and dramatic unborn, a population of aggressive parakeets, his great uncle who gave life to this sort of parallel hemisphere and, obviously, the mother. The meeting with a young Himi, still far from becoming her mother, becomes the essential element to understanding the meaning of her journey. Finding her means reconnecting to her origins, reconnecting with a brutally torn love story, and, precisely from that and from the awareness that it will never truly end, finding the strength to live again.

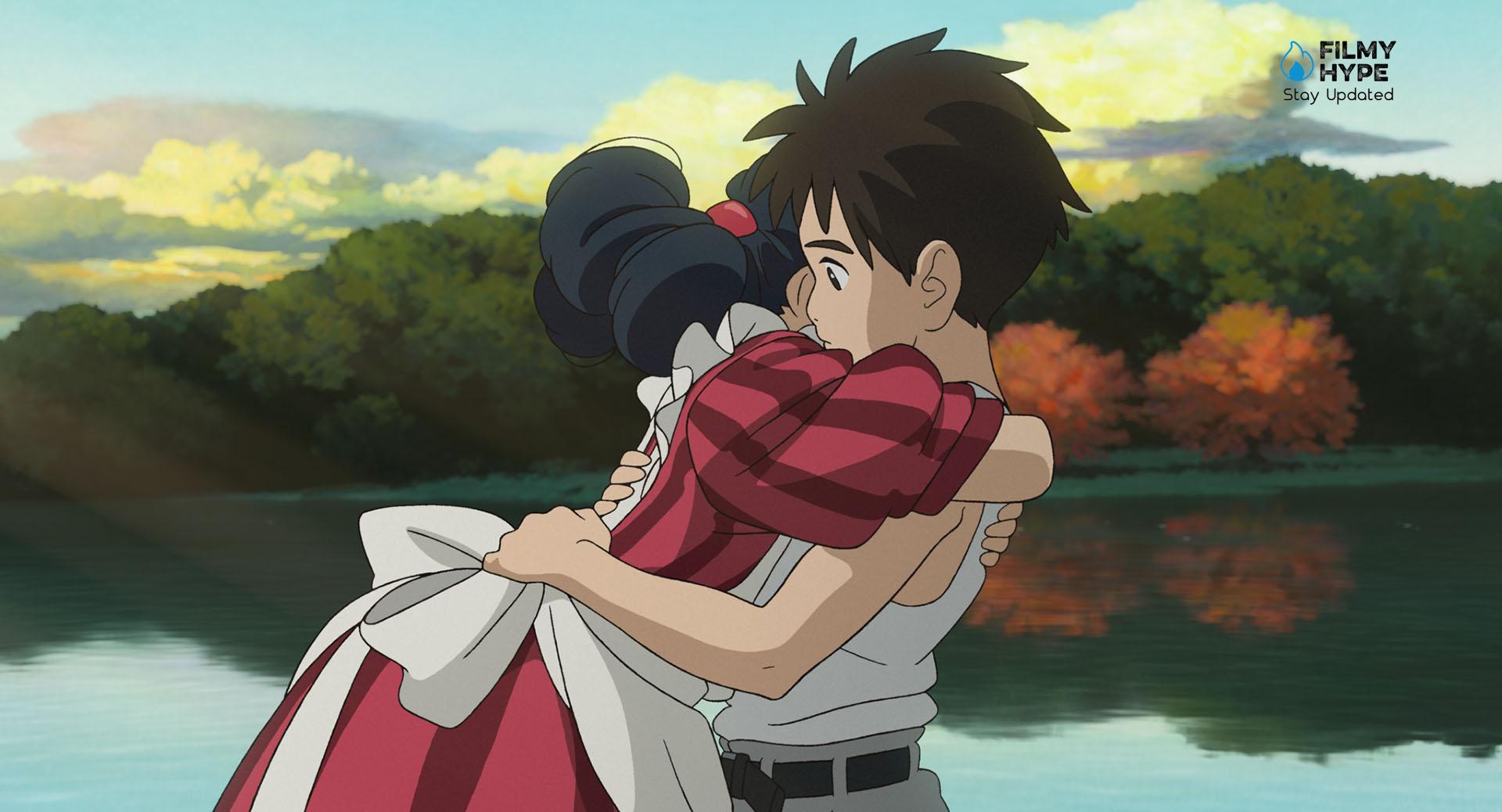

During the final stages of the film, Mahito is offered the possibility of becoming the heir of that mysterious world completely detached from reality. A possibility that he rejects and with it the danger of remaining forever clinging to his frustrations and barricaded in a hopeless solitude. Instead of him, however, he prefers life in a last-gasp race next to Himi while everything collapses around them. Both reach the doors that will lead them back to their present. But they are different for each of them. Himi returns to the period before the birth of her son. She is aware that she will die young but giving birth to Mahito is the drive that leads her to choose her destiny despite everything. At the same time, the boy decides to return to his life knowing that he will never lose that strong and indissoluble bond with his mother that he has rediscovered. Thus, leaving the tower, he returns to “see the stars” of his life, free from the weight of mourning that has finally been processed.

The Heron

In mythology, we speak of psychopomp, a word that comes from ancient Greek and represents the union of the person psyche (soul) and pompos (he who sends): it is, therefore, a divinity that acts as a ferryman, as it was Charon in Dante’s Inferno, just as he was Osiris for the Egyptians or Charun for the Etruscans. Herons in Japan have, in tradition, a meaning that traces their connection to spirits, and gods, as well as death and the passage to another world. The Kojiki, Japan’s oldest literary work, dating back to 712, contains a story about a prince who dies while away from his home, transforming into a white bird: no mention is made of a heron, but the description brings us back to right in front of a gray bird, which in itself is often depicted as a messenger of the gods and a symbol of death.

There is no shortage of representations in Japanese folklore, especially as regards Noh theatre, of white herons, which differ from those of other colors: the aosagi, blue in color, together with the goisagi, the nocturnal one, have a much more disturbing presence than to the pure white one and in some way, in his representation, Miyazaki wanted to pursue this restlessness. It is also the result of the fact that inside the heron hides a man who is not good-looking. The Heron thus becomes a symbol of a ferryman from one world to another, who may not necessarily be a leader towards death, but rather from a real-world to a supernatural one. Leading us into the context of death would be easy because, at the age of 83, Miyazaki could be afflicted by thoughts about the end of his life, but it could be too simplistic in reading, while the key linked to the fact that Mahito’s great-uncle says to the Heron of having to act as a guide on his journey.

Mahito – Great Uncle – Miyazaki

The figure of Hayao Miyazaki can be found in at least two characters at the same time. It is easy to compare him to Mahito Maki, the protagonist, due to a series of elements that reflect the director’s own life. Miyazaki was the son of an aeronautical engineer, owner together with his brother of Miyazaki Airplane, a company specialized in the production of rudders for Mitsubishi A6M fighters which allowed the entire family to live in comfortable conditions both during the war and afterwards. Planes had already been central to the plot of The Wind Rises, but they return here with a less cumbersome presence: we understand that Shoichi Maki, the protagonist’s father, works in a factory that follows aeronautical events and that does not want the production was interrupted during the war: their condition, certainly wealthy, allowed the family to escape from Tokyo during the Second World War and take refuge in a mansion in the countryside, complete with servants in tow.

Another element that characterizes Miyazaki’s life is linked to the fact that he remembers the bombings during the war in a very harsh way from his childhood: in 1944 his family was forced to evacuate first to Utsunomiya and then to Kanuma, to try to find serenity during the war period. Ultimately, Hayao’s mother – Yoshiko – suffered from spinal tuberculosis from 1947 to 1955, a disease that forced her to bed first in the hospital and then at home, we imagine forced into a controlled environment, to which it was not possible to access. An analogy to what happens to Natsuko, Mahito’s aunt, and the taboo of the delivery room inside the tower.

Much more difficult, however, is the parallel with Great Uncle: man finds himself having created a hypothetically healthy environment, built of 13 elements (Miyazaki’s films are 12, including this one, so the symbolism could come close, but not overlap), within which there are no wars, there are no diseases and there are no worries, except a normal course of events. Toshio Suzuki, producer of the film, spoke of a bond that pushed Great Uncle towards the figure of Isao Takahata, co-founder of Studio Ghibli together with Miyazaki and director with whom the association was fundamental for the Japanese artist, discovered by Takahata himself.

In the film, the man is looking for an heir and the crossroads presents us with a double choice: if the heir has been identified in Mahito, who is asked to work to put the world in order, then it could be a passing of the baton from one director to another; if, however, we wanted to interpret everything as a desperate attempt by Miyazaki to entrust his art to someone, we would have to review Mahito’s position, who could no longer be someone to whom Studio Ghibli would go. On the other hand, Miyazaki’s son himself has not, to date, been able to take up his father’s legacy. Furthermore, in all of this, the King of the parakeets arrives to destroy the entire constructed world, as an external figure extraneous to everything, but only intent on safeguarding the nature of his fellow men and his followers. Alternatively, since the film is dedicated to Miyazaki’s nephew, Mahito could be the latter, while the great-uncle would return to being the director. In short, a metaphor that can have numerous readings, merging into the one we deem most appropriate for our taste: after all, there is never a single reading of what we see and admire.

Dante’s Inferno

The third canto of Hell from Dante Alighieri’s Comedy begins like this: “For me, you go to the sorrowful city, you go to the eternal pain, for me, you go among the lost people. Justice moved my high factor; the divine power, the supreme wisdom, and the first love gave me”. When Mahito decides to follow the call of Heron and enter the tower he sees an inscription in front of him that reads “he made me the divine power”. Power, wisdom, and love are the attributes of the Trinity, with power being attributed to God, wisdom to the Son, and love being the Holy Spirit. With this inscription Miyazaki wants to welcome the protagonist of the film into what could be Dante’s hell, a set of circles that contain within them different types of people and condemned people, all placed there by the will of divine power. At the same time it could be a reference to himself, as if his art is nothing other than a will of God himself: after all, Miyazaki is a graduate of political science who approached manga and animation only in a second moment of one’s life, perhaps right after a divine flash. Mahito, in the meantime, faces a path that is equivalent to crossing a dark land, within which he has a guide – Virgil/Heron – and crosses a world within which he discovers all new aspects, as well as meeting people who he had already known under another guise in the world above.

The Symbolism of the Paintings

Two paintings immediately come to mind when watching The Boy and The Heron. The first is linked to The Castle of the Pyrenees, an oil on canvas by René Magritte from 1959, which drew inspiration from the island of Laputa which appeared in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. A very dear reference to Miyazaki, who in 1986 made one of his films concerning the island and used the same graphic representation that belonged to Magritte. A second painting is the Isle of the Dead by Arnold Bocklin, who between 1880 and 1886 created five different versions of the same image, full of symbolism. The painting itself has, within its body of water, a small boat approaching the island of the dead, led by a driver, a psychopomp, clearly inspired by Charon and – in this case – by Miyazaki’s Heron. At the bow of the ship, there is a mysterious figure dressed in white, who could be a soul or simply a symbolically pure, candid person: a sincere one, which is the meaning of Mahito’s name.

There is a lot of symbolism that links the narrative to death, to being ferried towards a new world, once again reiterating what could be the concept of a Miyazaki afflicted by advancing age and wanting to go and enjoy a well-deserved retirement. And that spirit of the tomb, which does not show itself, but which must not be awakened, that same door that is broken down by pelicans, hides something that we are not allowed to know and that we cannot go and discover. We just know that we have to be far away when he wakes up and decides to show up and be noticed. On the other hand, we are not allowed to know what lies hidden in death.

And How Will You Live?

We close with the inevitable final consideration dedicated to the novel and how you will live. It is a 1937 work from which The Boy and The Heron should have been inspired. Written by Genzaburo Yoshino, it follows the story of a 15-year-old boy, Junichi Honda, known as copper, fresh from having to face the death of his father and the consequent move to his uncle’s house, by the will of his mother. It is a coming-of-age novel, which Miyazaki used as a starting point, but which for the director himself represents a fundamental element for his training. Mahito, among other things, has with him a copy of the book, which among other things his deceased mother leaves him at the beginning of the film itself: what he has with him, however, is a different version from the one marketed in ‘ 37, and which was printed in Italy for the first time a few years ago.

The novel ended with a question from the author who asked the reader how he would decide to face his life from that moment on, based on what he learned during his experience of living with his uncle: the same Miyazaki film could hide the same message, after the journey inside the tower, to discover that world which could be identified as a dark forest to be explored and visited with more attention in the future. On the other hand, Mahito, unlike his mother returning from the trip, has not forgotten what he experienced and will be able to treasure it for his future.