Prometheus: The Past of Alien to Give a Future to the Saga?

Prometheus was one of the most loved movies from the Alien franchise. Going back to the origins of a myth is never easy. As demonstrated several times by various franchises, from Star Trek to Star Wars, trying to undermine the vision rooted in the collective imagination of a certain concept is a real challenge, which often leads to a rift in the fandom. A comparison that not even a living legend like Ridley Scott avoided, who, well before giving a sequel to his cult Blade Runner with Blade Runner 2049, had decided to rewrite the origins of another of his particularly beloved works: Alien. And this rewriting has a name that, for xenomorph enthusiasts, often turns up their noses: Prometheus.

Upon closer inspection, when Alien was released in 1978, the plot of the film was focused on the tension of a claustrophobic horror movie, leaving out the exploration of an environmental connotation that would make this future concrete and recognizable. Understandable, considering the nature of the film, which saw sci-fi not so much as an essential element of the narrative, but as a setting within which to adapt a standard horror idea. This aspect allows us to notice how Scott’s film also lacks some of his most cherished themes, developed later in other films (from Blade Runner to Prometheus), such as the relationship with the divine and coexistence with artificial intelligence. The focus of Alien was the anxious struggle for survival, so much so that the film could have been a perfect stand-alone film, but the success pushed Fox to give life to a franchise, starting with James Cameron’s Aliens he inserted the xenomorphs into a completer and more defined narrative dimension. A detailed portrait that however failed to tell a fundamental element: the origin of the xenomorphs.

Prometheus: The Origins of Life

Starting from Alien the presence of lethal aliens is given as axiomatic, they exist, and we must not ask ourselves questions about their origins. In reality, Scott had initially conceived a more complex narrative that also addressed this theme, so much so that with his two closest collaborators of the time, HR Giger and Dan O’Bannon, he had created a series of narrative branches that also explained The origin of another figure who has become a legend in Alien continuity: the space jokey. The mysterious alien found inside the extraterrestrial vessel in Alien had remained in the collective imagination as a figure cloaked in mystery, whose origins had subsequently been explained in the comics sector with Alien, a series entrusted to Mark Schultz in which to continue the narrative of the saga after the events of Aliens 1986 and become part of the Aliens Universe, a gigantic what if…? Following the release of Fincher’s ALIEN³.

An opportunity that therefore allowed Scott to have numerous questions available to work on to lay the foundations of his future universe. Approaching everything as a prequel was certainly nothing new for Hollywood in the early 2000s, after Lucas had taken this path to complete Star Wars with the Prequel Trilogy, starting with The Phantom Menace. Scott, intending to follow this example to definitively impose his vision on his narrative universe, therefore decided to tell the genesis of the clash between humans and xenomorphs, starting from an extremely fascinating element: first contact.

The idea was certainly intriguing, but at the same time dangerous. Much of the charm of the xenomorphs was linked, in fact, to their aura of unfathomable mystery, a feral ferocity arising from the depths of space that had made them both fearsome adversaries and a coveted object of study, especially by Weyland-Yutani. Depriving the xenomorphs of this peculiarity of theirs to tell their origins was a gamble, but it must also be credited to the director who now found himself managing his own creation after decades of more or less successful sequels, unlikely team-ups (like Alien Vs Predator) and a decidedly prolific multimedia treatment of one’s alien.

It was therefore time to bring some order to the saga, and there couldn’t be, in Scott’s opinion, a better way than to go back to the origins. Prometheus was born precisely in this spirit, an idea already sketched out by Scott in 2002 but which was later frozen after the less-than-enthusiastic box office result of Alien Vs Predator. At first, Scott wanted to make a sequel to Alien, which would be placed between the first film in the saga and Aliens 1986, to tell the origins of the xenomorphs and reveal the identity of the gigantic pilot of the alien spaceship, the infamous space jockey. Also giving support to Scott was James Cameron, who proposed to help his English colleague, at least until 20th Century Fox tried to tease the director of Titanic with the idea of instead directing a crossover that would put the two in competition with lethal aliens from the major label, Alien and Predator.

Cameron immediately understood the danger of this operation and decided to abandon the project, convinced that this clash between aliens would have significantly damaged the Alien franchise. A choice that demonstrated its validity with the failure of Alien Vs Predator, and which pushed Cameron to refuse further collaborations on the franchise, which the director considered dangerously subject to unpleasant interference from the major. If Cameron had distanced himself from this project, Scott was instead firmly convinced of his ideas. So much so that in 2009 Fox announced what was initially conceived as a reboot of the saga, which stopped when Scott refused the director’s chair, a choice disliked by Fox who tied the making of the film to Scott himself directing, with the screenplay entrusted initially to John Spaihts, who had a seemingly simple task: answer the big questions of Alien.

Not Just Xenomorphs

Having officially become a prequel, the idea of a reboot was quickly abandoned, and the film that would later become Prometheus had to tackle the original mysteries of the saga. For Spaihts, this meant finding a point of contact between the alien figures at the center of the puzzles and the human dimension of the protagonists, a delicate balance that the screenwriter clearly identified:

All the questions are based on alien characters: the nightmarish exoskeleton and the elephant-like titan called the space jockey. How do you get someone to take an interest in such creatures? What if their story was somehow linked to ours, if it were intertwined with the history of humanity, what if this story radically changed the meaning of existence itself, touching on concepts so fundamental that they could change our very conception of life?

Based on this intuition, Spaiths developed a first draft of about twenty pages which he submitted to Scott at the end of 2009, which found the director’s approval. Scott himself, stimulated by this idea of a bond between different races, made some corrections to Spaiths’ script, sending some suggestions to the screenwriter on Christmas Day 2009. Central to this first revision was the theory expressed by Erich Von Däniken in his volume Chariots of the Gods, which hypothesized that life on Earth was created by ancient alien astronauts, a vision that impressed Scott, so much so that he strongly supported it for his film:

The Vatican and NASA agree that it is almost mathematically impossible that we could be where we are today without having received a little help along the way. This is what we are trying to tell in our film, accepting some of Von Daniken’s ideas on how we humans appeared

A theory that will lead to the birth of the figure of the Engineers, the colossal aliens who bring life to Earth in the first scenes of the film, and who will be central in the creation of the xenomorphs. This step of the screenplay process will be essential because it will become the foundation for the entire narrative plan of Prometheus, especially when Scott entrusts Spaith’s script to Damon Lindelof’s final revision. It will be Lindelof himself who understands an apparent limit of Prometheus: we already know where it will end

If the ending of Prometheus had been inside the chamber where John Hurt finds the alien eggs, there would have been nothing interesting, because we would have already known where the story would end. Compelling stories are the ones where you never know where you’ll end up. A prequel verse should essentially precede the events of the original films, but at the same time be completely different, feature different characters, and have different themes, despite taking place in the same world

Starting from this idea, Lindelof spent five weeks reworking Spaiths’ screenplay, trying to enrich the typical themes of the Alien saga, such as the claustrophobic horror and the action nature of its sequels, intertwining them with the narrative ideas of another very popular work. Scott’s beloved: Blade Runner. Upon closer inspection, already in Aliens and Aliens 1986 the relationship between humans and artificial life forms had clearly materialized, just think of the figures of Ash and Bishop, but Lindelof’s intuition was to transform this coexistence by introducing psychological elements that were an echo of what was seen in Blade Runner:

Blade Runner may not have been a big box office success when it came out, but people still talk about it today because it was full of big themes. Scott was thinking about important themes for Prometheus too, he was guided by people who wanted answers to the big questions. I was convinced that we could achieve this without being too pedantic. Nobody wants to see a movie with people floating in space talking about the meaning of life, this was already evident in Spaiths’ script, and Scott just wanted to bring it out a little more

Prometheus was no longer a simple prequel to Alien, but increasingly became a journey among the stars to discover the origins of humanity itself. A strong narrative identity was therefore enriched with themes of a certain depth.

From Milton to Greek Mythology

Scott originally titled the film Paradise. The reference was to Milton’s Paradise Lost, a work with a strong philosophical content in which human nature is explored through a religiously tinged metaphor. This idea did not fully convince Scott, who found the solution on the advice of Fox’s top management, who pushed the director to look at the Greek myth of Prometheus, the god who, challenging Olympus, granted men the knowledge of fire, being punished with torture infinite. According to the myth, divine hatred was due to the fear that with knowledge men could challenge the very power of the gods.

The spirit with which the expedition at the center of Prometheus ventures among the stars seems to embody this divine fear. Driven by the need to discover the origin of their species, the crew of the Prometheus sets out in search of their creators, but behind this apparent thirst for knowledge, lies the basest desire to obtain immortality, to rewrite the concept itself of being human. Strengthened by this fascinating suggestion, Scott based the figure of the Engineers on a sort of divine model. His request for the make-up was to make these aliens similar to the visual ideal of Greek iconography, but also conceptually made the Engineers divine-like beings.

So much so that initially it was thought to refer to an Engineer who had arrived on Earth about 2000 years before the events of Prometheus, to put a stop to the violent and petty human race, alluding to the figure of Christ, whose crucifixion should have taken the sense of an act of defiance against this alien race. A strong choice, which Scott had strongly pushed on this detail, only to then understand his danger:

We thought so, only to then think that it was too perfect. In my mind I have always seen the Engineers as some sort of deities, creatures similar to God, but not as beneficial, and ultimately not so divine. I had always been clear that I would make a sequel, and meeting God already in this first chapter seemed wrong to me, I wanted Shaw to be able to choose not to go back, but for her to choose to go where they came from!

Despite this choice to avoid the divine definition of the Engineers, Scott still gave them the role of bringers of life, as evidenced by the exciting prologue in which one of the aliens sacrifices himself to bring life to a barren planet. A world that we are led to identify as Earth, but which Scott himself wanted to shroud in an aura of mystery:

The opening sequence of creation is a gift, it shows the importance of these creatures. We are not necessarily on Earth, we could be anywhere, the relevance is in the gesture, of bringing life into the universe by choosing to die for this purpose.

Yet, the concept of faith is central in Prometheus, not only for the obvious quotes and references but also for the very conclusion of the story, which sees the big questions still left unanswered. It is no coincidence that the only character with an obvious religious connection, Shaw, is the only survivor, capable of accepting the scientific origin of humanity, feeling almost relieved, but still able to believe in a superior entity. His departure at the end of Prometheus to continue this search for primordial truth is at the same time a monument to human curiosity, the basis of science, and an affirmation of faith, in a rare example of the coexistence of two such antithetical elements.

A mission animated by the search for answers to the great questions of existence, linked to our origins. Prometheus bases its dynamics on the concept of creation, from the first images, with the sacrifice of the Engineer for the creation of the human race, continuing throughout the film with a cycle of forced procreation which, in a closing of the circle, takes us back to the Engineers themselves, after a series of alien fertilizations involving both the human race and that of their creators, a mechanism set in motion, ironically, by the only non-biological life form: the android David. The android excellently played by Michael Fassbender once again embodies the disruptive technological element within the plots of the Alien saga. Ash had a malfunction during his secret routine to recover the alien eggs, Bishop shows a morbid curiosity during his autopsy on the face huggers in Aliens 1986, showing how synthetics are always disturbingly linked to the concept of life, understood as birth and continuation of the species.

It’s hard not to notice how this internal worry about synthetics is reminiscent of the desperate search for ‘more life’ by Roy Batty and company in Blade Runner, even if it is addressed differently in Prometheus. If in Blade Runner the synthetics’ yearning was for their awareness of imminent death, combined with the knowledge of their origins and its acceptance, for David in Prometheus this curiosity pushes in the direction of why exist, in a vision that seems to shun the Cartesian axiom.

David is aboard a ship full of human beings trying to understand the why and origins of their existence, and he doesn’t initially seem to understand their need. The events of the film will be useful for him to get closer to this curiosity, to the point that he will finally choose to follow Shaw on her journey among the stars. A wealth of nuance, well inserted within the plot of Prometheus, which Lindelof explained very clearly when presenting the narrative aims of the film:

You are exploring the future, far from Earth wondering what people will be like. Space exploration in the future will evolve into a vision that will not only be tied to the idea of going into space and finding new worlds to colonize but will also have the innate idea that the deeper we delve into the cosmos, the more we will learn about ourselves. themselves. And the characters in this film are animated by a precise question: what are our origins?

The Future of Prometheus

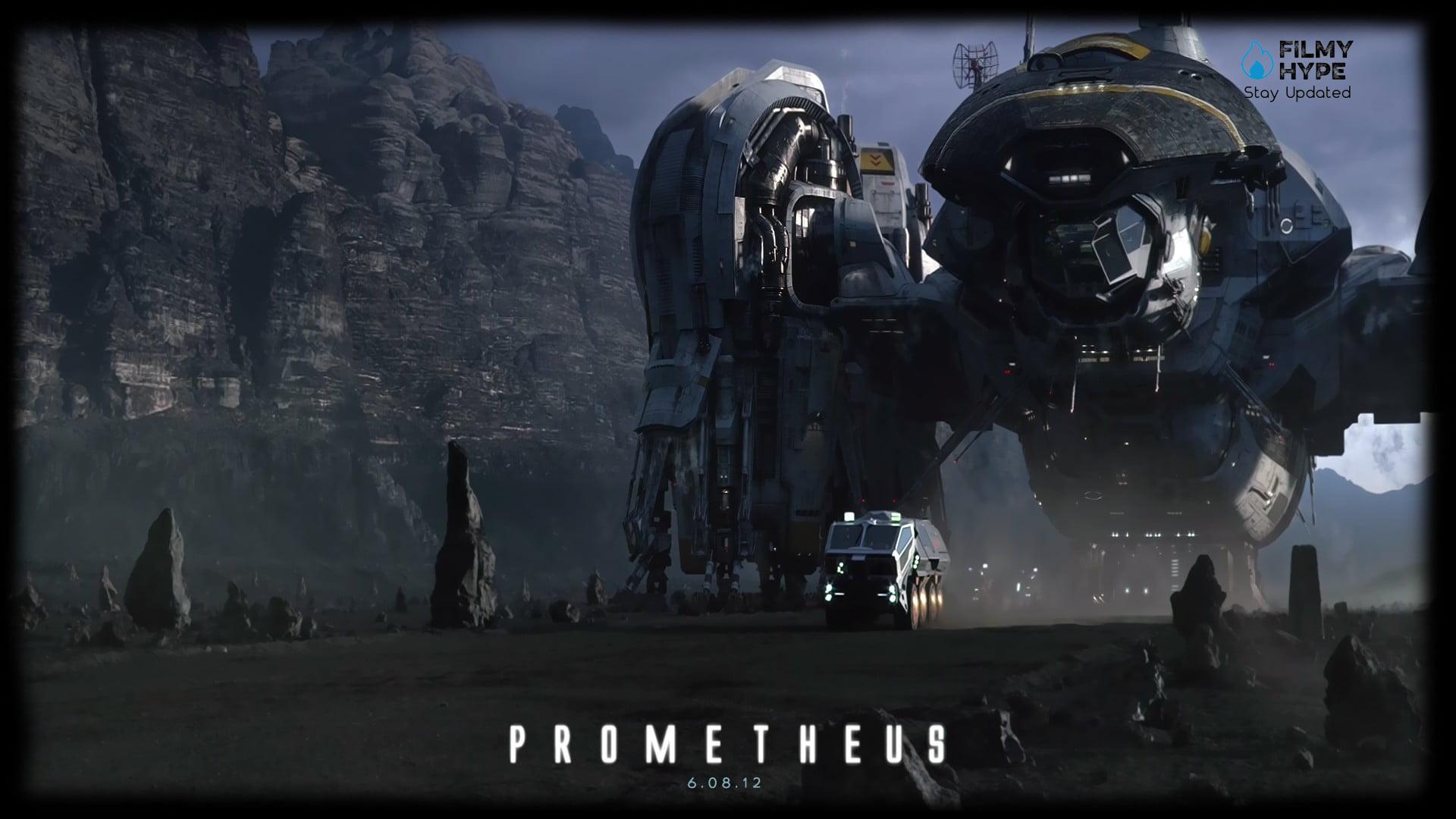

Even though it was a prequel to Alien, Prometheus had found its own identity, a fusion between the search for answers to the questions that emerged in the inaugural film of the saga and the need to start new plots. A search for a personality that also extended to the visual definition, to the technology of future humanity, which did not find a worthy representation only in David. Suffice it to say that Arthur Max, in charge of creating the sets dedicated to the Prometheus and the Engineer’s ship, spent time studying the theories and projects of NASA and ESA regarding the design of colonizing spaceships, acquiring skills and ideas which he inserted into of their work. The obsessive care in portraying credible technology also gave life to the astronauts’ equipment, a synthesis between functionality and conceivable technological evolution. Scott aimed, for example, to create helmets that were transparent, convinced that by 2083 technology would allow the creation of highly resistant transparent materials, with which to create a helmet that would allow an open view, unlike the restricted one of current cosmonauts.

What is also interesting in this process of genesis of the world of Prometheus is the idea of recovering previous intuitions never used in the saga. Already at the time of the first script for Alien, Scott, and O’Bannon had created a sort of alien protoculture, including rituals for the fertilization of xenomorphs, going so far as to create an architectural style, entrusting the disturbing artistic flair of HR Giger. An almost recovery operation, considering that the Swiss artist had re-adapted the techno-organic concept developed at the time of his collaboration with that incredible artistic think tank led by Alejandro Jodorowsky assembled to create the first, pharaonic and never made transposition of Dune. What should have been Harkonnen Castle had become, at the time of Alien, an alien temple, but when the social definition part was radically cut, in favor of a more claustrophobic narrative with a different tone, Giger’s ideas ended up in mothballs, being only later recovered by Scott for the creation of Prometheus, becoming the basis of the Engineers’ culture.

The Beginning of a New Era for Alien?

Despite being included within the Alien saga since its genesis, Prometheus has a peculiarity: Alien is never mentioned, neither in the synopsis nor within the narrative. The world is unequivocally the one made famous by Ripley, as demonstrated by the presence of obvious references, but it is interesting to note how we tried to follow the search for an independent identity for this film compared to the established fixed points of the saga. Lindelof’s thoughts in this sense were clear, as we have seen, but it is equally important to remember that, in the early stages of production, the nature of the film was still in doubt: reboot or prequel? The confusion was finally resolved with a return to the origins, which also wanted to be a new beginning for the saga, plagued by the presence of little-appreciated chapters, such as ALIEN³ or Alien: The Cloning. Scott himself had a very precise idea about the route to follow:

Alien is the obvious starting point for this universe, but from the creative process, a huge new mythology, a universe in which this untold adventure takes place. Fans will find strands of Alien’s DNA, but the issues we address in this film are specific, important, and divisive. I couldn’t be more satisfied in having identified the story I was looking for, finally being able to return to a genre that I feel particularly dear to me

Prometheus, upon closer inspection, is not a standalone film, unlike Alien. It is clear that the greater wealth of suggestions infused into this film by Scott, and probably more so by Lindelof in his rewriting of the plot, were aimed at creating the first chapter of a broader narrative. A sort of compromise between creator and spectator, with an answer to some doubts linked to the parent film that takes on the tone of a new question that projects us on a different route compared to what we experienced previously. A concept that clashed with the Alien fandom, which, starting with Prometheus, criticized Scott’s return to the saga. It is certainly not the first time that a prequel has encountered stubborn criticism from fans of a series, it would be enough to mention the less-than-warm reception obtained by The Phantom Menace among Star Wars enthusiasts, but it must be recognized that the heavy criticisms leveled towards Prometheus are, in some cases, born more from a sense of damaged possession on the part of the fandom than from an intrinsic criticality of the film.

Being the first step of a broader journey, set in the already well-known Alien universe, Prometheus had the task of rebuilding a bond between fans of the saga and its new, different dimension, animated by a different concept of sci-fi compared to his most esteemed predecessors. Alien had more features of a horror movie, while Aliens – Final Clash was stimulated by a vision of war science fiction, with Prometheus Scott intended to create a more emotional narrative with philosophical traits, totally absent in the saga up to that point. Prometheus, like the homonymous protagonist of the Greek myth, brings a new spark into the saga, knowledge, both as a possessed notion and as a search for it, giving a different impetus to the saga. Scott’s film suffers from chapter one syndrome, the creation of an in-depth world later on, compounded by fans’ supposed familiarity with this setting.

A sense of nostalgic affection disappointed by the radical transformations of the world portrayed by Scott, who did not hide his desire to lay the foundations of the chronology of his saga, giving life to his own universe. A narrative context which, according to some theories, would be shared with his other great creation, Blade Runner, thanks to a textual reference in the extra contents of the home video edition, in which it was told how Weyland’s idea of creating androids was born together with an old acquaintance of hers, who later created these human simulacra from the city of angels (nickname of Los Angeles), where she lived in a gigantic pyramid. It’s difficult not to think back to Eldon Tyrrell and his pharaonic palace seen in the first Blade Runner. Net of these speculations, the fury with which part of the Alien fandom has lashed out against Prometheus seems excessive, an aversion that seems to find much of its foundation in the following chapter, Alien: Covenant.