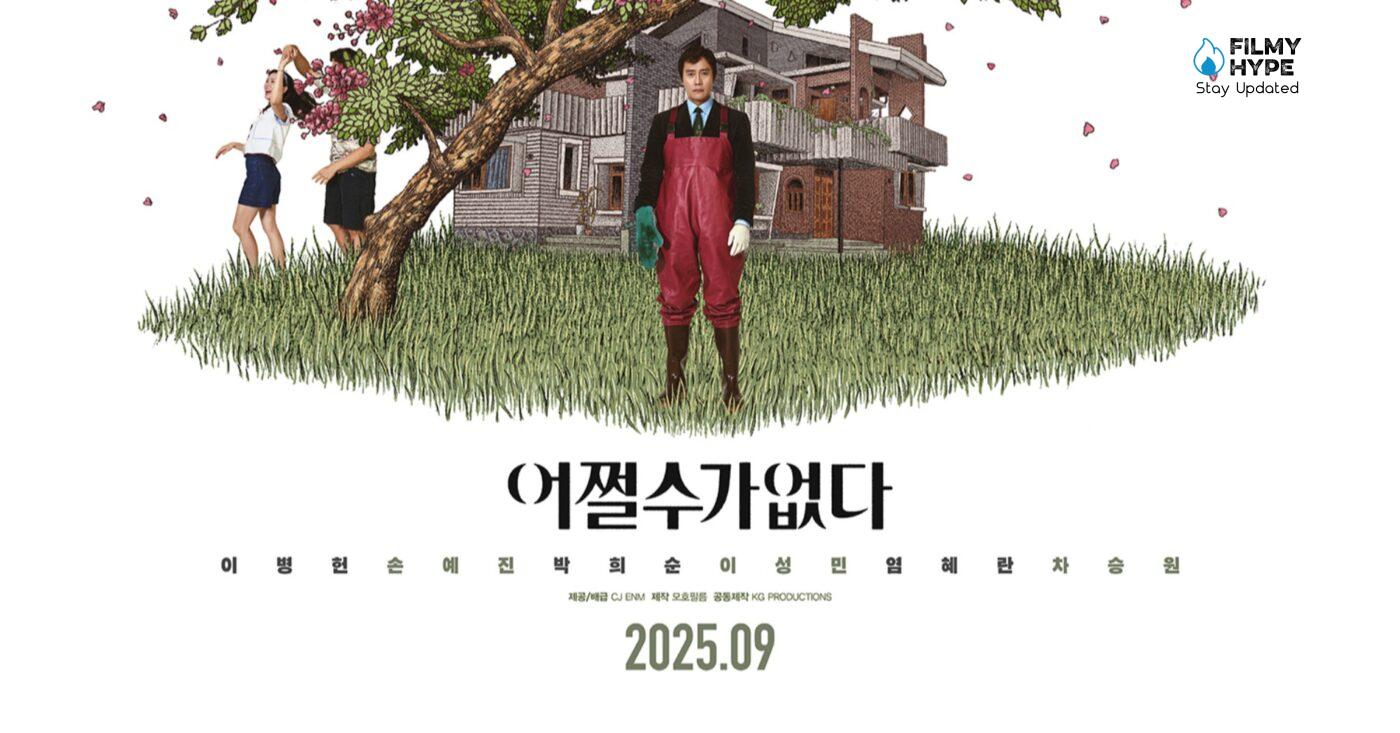

No Other Choice Movie Review: Universal Drama, Between Social Criticism, Emotional Tension (Venice Film Festival 2025)

No Other Choice Movie Review: Presented in competition at the Venice Film Festival, No Other Choice is the new, highly anticipated film by Park Chan-wook, one of the most authoritative masters of contemporary cinema. After signing titles that have become milestones such as Oldboy, The Handmaiden, and Decision to Leave, the South Korean director returns with a work that weaves together social drama, psychological tension, and a staging of rigorous formal perfection. Loosely based on the novel The Ax by Donald E. Westlake, the film tells the story of the fall of an ordinary man, transforming a personal story into a universal reflection on our time. One thing that is always evident when we look at the works of great authors is the ability to observe and talk about the world around them, to grasp the signals and anticipate the times, so that their works are current at the time of release.

No Other Choice is a confirmation of this, because it is a project imagined a long time ago (twenty years, from what Park Chan-Wook says in the director’s notes), but capable of telling the difficult present we live in, where to be told that “there’s No Other Choice” has become a bitter custom. The inspiration came to the director by reading the novel The Ax by Donald E. Westlake, identifying with the protagonist and his passion for paper. A passion that he felt, equally overwhelming, for cinema, so much so that it put him in total harmony with the character. An idea that remained there and sedimented, becoming the completed, mature, and original work that we appreciated in the Venice Film Festival number 82, which surprises us with the first titles presented.

No Other Choice Movie Review: The Story Plot

For Man-soo (Lee Byung-hun), life seems to be perfect. For 25 years, he has been one of the best employees of a very important Korean paper industry. He has an excellent salary, with which he keeps his wife, stepson, daughter, and two dogs in his dream home. There is only one problem: his company was bought by an American multinational, which decided to inaugurate the merger with a wave of layoffs. When he discovers that he is among the purged, Man-soo goes into total crisis. In the following three months, he is unable to find or keep any jobs, even being forced to give away the dogs, sell the cars, and finally accept the fact that perhaps he will even have to leave that house. Literally enraged by what happened, the man gradually becomes convinced that there is only one solution: getting hired by a Japanese paper giant, killing the current foreman, whom he accidentally passed in a bar. But it won’t be enough to eliminate that man to succeed in his aim at Man-soo, to regain his self-respect and his dream life.

He will also have to kill all those who, in a possible job interview, could pass in front of him. Between doubts, second thoughts, disasters, and snake bites, Man-soo will try to fulfill his mission: defend his lifestyle. “No Other Choice” marks the great return of one of the directors who has allowed Korea the most to become an absolute point of reference in this 21st century on both the small and big screen. As in his Trilogy of Vengeance, here too we have a man dealing with something unexpected; there is an avenging will which, however, here is against an economic, social system, which he does not deny, but rather about pursuing faithfully. The protagonist’s choice is theoretically atypical, given that Lee Byung-hun made a name for himself especially in action films, but here he proves that he is simply perfect for the part. Man-soo, selfish, childish, locked inside that house-castle which is the symbol of his materialism, of his narrow-mindedness, will start a personal crusade that will mix ridicule with the sadist.

No Other Choice Review and analysis

Korean cinema and television in this century have become a symbol of civil and social denunciation, and “No Other Choice” is no exception. The Korea shown to us here is a cruel, narrow-minded country, where corruption, nepotism reign supreme, where consumerism is the only real reason for living. But it’s something we could ultimately use to describe every modern country. Park Chan-wook destroys all the pillars of society: the family, the home, and work. No one is saved; the children themselves are a portrait of unbridled ambition, on them fall the sins of parents, convinced that only by coming first, passing over the bodies of others if necessary, can happiness be achieved. Chan-wook visually structures the film following very precise geometries; it’s the interiors that count, those of Man-soo and his victims. Each house tells us a story and a part of the personality of these men who, having lost their jobs, feel useless, powerless, and purposeless. The criticism concerns turbocapitalism, artificial intelligence, but also the working class.

There is something about Petri’s cinema, Germi, but also a Chaplinian infuriation in the impact of this man who became a hitman, determined to destroy the lives of others who, like him, are linked to his own virility, the meaning of his own life, and to your salary. “No Other Choice” is a story that contrasts day with night, inside with outside, above with below. We have lush plants and trees, feeding on the skeletons in the closet, on the crimes committed by a nation that, even today, does everything to make its citizens robots. However, the whole thing always remains fun, truly entertaining, with jokes, twists and turns, a sense of the ridiculous that dominates every minute, every moment. Chan-Wook confirms himself as an author capable of making us understand that life today is a race against everything and everyone. So far, the best film of Venice 82 with the best male performance, a demonstration of how Korea is a separate discussion, of how this country remains perhaps the last fortress of that cinema capable of surprising, of delving into the spirit of our era.

What are you willing to do to support your family and not give up anything? Squid Game has brought us the answer with the invention of these deadly games, a horizontal fight where dog eats dog for the lavish loot obtained once he has passed all the tests. With No Other Choice, we are on the same common thread, but the methods and context change. Park Chan-Wook will have succeeded in putting a different stamp on the desperation within Korean (almost American) capitalism It all begins when the protagonist Man-soo is fired after 25 years of honorable work: two children (one not his), a wife, two dogs, a beautiful house and a personal greenhouse, this is what is at stake once he finds himself unemployed. It seems like a plot already seen and written, that of the average man who suddenly finds himself on the ground and forced to fight to get everything back.

It’s a shame not to be in an action, because Park doesn’t want to play with the revenge of a human being, but with his desperation. There is No Other Choice, the protagonist continually repeats within the film, because the world of work represented in the film is constantly evolving, transforming to make room for more and more new technologies and the increasingly reduced and replaced hand of man. Yet Man-suu doesn’t agree, he intends to resume his life for the future of his family, even willing to kill his competitors to have a guaranteed place in the paper industry, an area in which he was part for a quarter of a century of his life. But things will not go as planned, triggering a series of events that will also shape family relationships. It will therefore be this obsession of his, a theme always dear to Park Chan-Wook, that will lead him into self-destructive ways to get his job back.

It could have been a cruel world recreated by Park, given his filmography, but what passes on the big screen of the Great Hall is not what was expected. Although the touch of the South Korean director makes the film one of the best on a technical-visual level through fades and never-predictable scene changes, the staging in some places is parodic. As much as one can observe how Man-Soo is an inept person who cannot eliminate a single person, there has been too much of a hand trodden on his smile. Coming from Decision to Leave, it seems hard to believe. No Other Choice is the story that follows two parallel tracks: the first is already known, and there is no need to repeat it, with Man-Soo and the consequences of his choice, derived in turn from the desire of others to remove him from his workplace; instead, the second is life in a ruthless Korea. The already ruthless Squid Game was able to take the place of those situations in which we really hit rock bottom, but Park’s new film shows the public a familiar microcosm put in difficulty, with all the sacrifices and small precautions to achieve maximum savings, whether it’s a tennis lesson or a cello lesson. What comes into Man-Soo’s family is a tsunami that completely devastates the lives of the entire nucleus, of which it is only one cell within the Korean social organism.

As in Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, also in No Other Choice, the individual drama becomes the reflection of an entire system. The story was born in the heart of Korean society, but it expands to speak to the whole world, telling the crisis of a social model that can no longer sustain itself. If the individual once found his or her identity within the collectivity, today, an exasperated individualism dominates, in which the well-being of one’s inner core justifies any gesture. The ferocious capitalism painted by Park Chan-wook is the same as in every corner of the world it devours, abandons, and forces those left behind to transform into predators to survive. Park Chan-wook’s direction is, as always, a precision machine. Each shot is designed to tell more than you show, each cut is calibrated to amplify the tension, and the editing alternates moments of quiet with sudden emotional explosions, building a rhythm that keeps the viewer on constant alert. The only real flaw is the duration: two hours and twenty which, in some passages, could have been shortened without affecting the strength of the story. But even in the most dilated moments, formal coherence and visual elegance capture and never let go.

Lee Byung-hun offers an extraordinary interpretation, giving his Man-su the dignity and fragility of an ordinary man. It is in the low gazes, pauses, and silences that the protagonist’s metamorphosis takes shape: from a professional proud of his work to a father willing to sacrifice everything to save what remains of his life. Next to him, Son Yej-in delicately and realistically outlines the character of his wife Miri, a woman who observes with love and helplessness her husband’s slow slide towards the abyss. Family is not a side element, but the driving force behind Man-su’s every gesture. It is for the children, for the wife, for that house conquered with years of sacrifices, that man decides to resist at any cost. But the system crushes him with growing humiliations, until the symbolic scene like Moon Paper, when the line manager arrogantly rejects him. It is there that wounded dignity becomes anger, and desperation becomes action. Park Chan-wook observes all this with surgical clarity, without ever indulging in melodrama, returning to a story that is intimate but at the same time universal.

No Other Choice is not just a title, but a sentence. It tells of a system that progressively reduces possibilities until they are erased, forcing the individual to move on obligatory tracks. In the world told by Park Chan-wook, work is not just a profession: it is identity, status, and dignity. And when all this fails, collapse becomes inevitable. This is where dedication turns into obsession and passion into violence, in a spiral that leaves the viewer with a disturbing question: was there really No Other Choice? With No Other Choice, Park Chan-wook signs a painful and very lucid work, capable of surgically narrating the drama of a single man and, at the same time, that of an entire society. It is a film that does not grant consolations and does not seek easy answers, but which observes with empathy and ruthlessness a world in which a person’s value is measured only by his productive role. Some narrative dilation does not affect its impact: what remains, in the end, is a powerful work, universal and destined to cause discussion for a long time.

You Man-su’s passion for paper is total, visceral, so much so that it becomes an obsession. Something positive, an emotional engine that becomes a reason for living, but which, once disillusioned, slips into worry, becomes a fixed idea, and degenerates into a nightmare. And this often leads to extreme, senseless, and questionable choices. It is a feeling that Park Chan-Wook understands perfectly, because it is what he feels for the seventh art but which he manages to concentrate in a lucid and balanced film, perfect for a solid but never cold staging: the director welcomes us into the world of No Other Choice and it guides us through the unexpected and tragic turns in the life of its protagonist, a very good Lee Byung Hun, dramatically keeping us on edge for what is his destiny. Without ever giving up, keeping alive that glimmer of hope that allows him, and us, to continue breathing and continue the journey of this story.

We watch the film and we are hit hard, because what happens to the protagonist is so realistic and concrete: losing your job means having to give up keeping the house of cards of our existence standing, a house whose mortgage is being paid, to the little luxuries we indulge in, tennis lessons, or any other activity we like to do. It’s like this for You Man-su and his wife Miri, but it would be like this for each of us, which is why the film strikes and involves us, which is why it speaks to us with splendid power. And it also does so with the times and ways of an impeccable staging, in which Park Chan-Wook confirms his mastery with the medium, consistent with his approach, but measuring excesses without ever overdoing it, leading us along the tragic path of the protagonist alternating more tense and extreme moments with ironic ones or still capable of a tender affection for his characters. No Other Choice is the confirmation of a great author who looks ahead to the dangers that new technologies and the developments of our contemporaneity represent for our normality and our security, relying on the warmth of something ancient, consolidated, and pure like paper, and our passions to remind us where to go to find certainties and hope. Assuming there is still a choice.

No Other Choice Review: The Last Words

No Other Choice by Park Chan-wook, presented in competition in Venice, is a powerful and universal drama. Through the fall of Man-su, an ordinary man who loses his job after 25 years, the director recounts the collapse of identity and the brutality of a system he devours and abandons. With pinpoint direction and a stunning performance by Lee Byung-hun, the film explores the shift from collectivity to extreme individualism, turning a Korean affair into a mirror of the entire world. Some narrative expansion does not undermine his emotional strength and formal precision, once again confirming the talent of one of the greatest contemporary masters.

Cast: Lee Byung-hun, Son Yej-in, Park Hee-soon, Lee Sung-min, Yeom Hye-ran, Cha Seung-won

Directed: Park Chan-wook

Where We Watched: At the Venice Film Festival

Filmyhype.com Ratings: 4/5 (four stars)