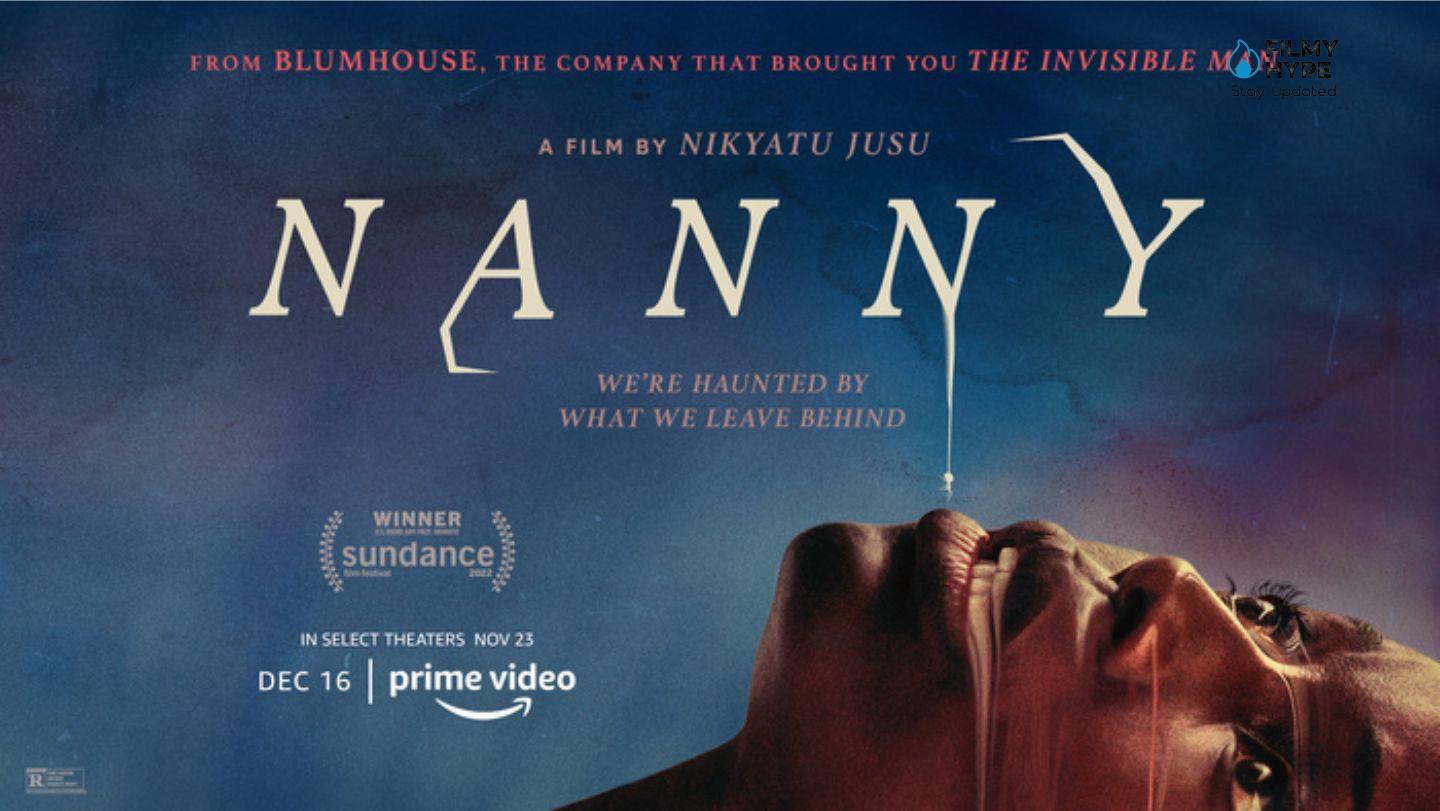

Nanny Review: Prime Video Film Manages To Bring Fascinating Imagery To The Screen

Cast: Anna Diop, Michelle Monaghan, Sinqua Walls, Morgan Spector

Director: Nikyatu Jusu

Streaming Platform: Amazon Prime Video

Filmyhype.com Ratings: 3/5 (three stars)

Arrives on Prime Video Nanny, the psychological horror presented at the Sundance Film Festival. The film directed by Nikyatu Jusu (in his directorial debut) is capable of captivating the audience by bringing to life on the screen a unique imagery, rooted in African folklore and the beliefs of its protagonist, but fails to capture as much as it should for a narration with a too relaxed pace and without the right bite. As we will see in this Nanny review, at the center of this story is Aisha, a babysitter of Senegalese origins who would like to realize the dream of bringing her son to the United States.

The story that sees her as the protagonist revolves around various themes, but mainly it is linked to her motherhood which is denied to her and to the consequences that her detachment from her child has on her psycho-emotional balance. Jusu, who is the daughter of an immigrant from Sierra Leone who worked as a domestic worker, manages to paint with decidedly clear and incisive brushstrokes the reality lived by Aisha and all women like her, forced to raise other people’s children while they’re waiting for them at home. Too bad, however, that if on the one hand, the film is striking for the portrait it makes of the inner world of this category of people.

Nanny Review: The Story

Aisha (Anna Diop) is a young Senegalese immigrant who, after abandoning her old life in her home country, is trying to build a future for herself in the United States. Together with the new job as a babysitter for a middle-class family – the mother Amy (Michelle Monaghan) is a career woman, and her husband Adam, played by Morgan Spector, is a distracted and not very present war photographer – also comes the possibility of making a dream: to bring his son Lamine to live with him.

Initially, everything seems to go well with little Rose, but over time the woman will begin to be haunted by nightmares and strange visions, something supernatural – which only she can see – seems to have targeted her. From Senegal, terrifying entities and magical creatures seem to have followed her: do they want to punish her for having left Lamine behind? Or is it the guilt that the woman tries to manifest itself in this way?

Nanny Review and Analysis

In addition to its ability to effectively represent the life of today’s immigrants in a foreign country, the other advantage of the film is that of mixing African folklore with history, bringing to the screen a unique and in its way extremely fascinating imagery. The figures of Anansi and Mami Wata – both symbols of resistance and survival for oppressed people – provide an interesting interpretation of what happens to the protagonist, stimulating the viewer’s curiosity. Bringing them into the almost aseptic, gray, and cold context of the home of her new employers is capable of creating an original and striking contrast.

Aisha’s American dream gradually shrinks, highlighting the true nature of the family she works for: on the one hand, the detached Amy, who, despite proving to be courteous, treats her condescendingly, never paying her what she should, on the other her father Adam, who acts too friendly, but who is completely disinterested in the family and the problems that afflict it. This a realistic representation of the situation experienced by many women like Aisha, at the mercy of a white society that exploits them for its convenience. This is where Anansi and Mami Wata come into play, morally gray entities who perfectly embody the anger of those who are unjustly subjugated.

A partially extremely intriguing narrative but which, as we initially anticipated, fails in what should be the primary purpose of a film of this type: building tension, thus involving the viewer. The more purely horror part of Nanny is flat and not very incisive, leaving those looking for thrills and emotions decidedly disappointed. Even the conclusion, which should be the climax moment in a story of this type, does not have any kind of bite, it is a bit rushed and less interesting than the ideas scattered throughout the film would have predicted. A real shame, because if the film Nikyatu Jusu hadn’t neglected its scarier side to focus solely on social criticism it could have been very memorable.

Nanny becomes a poignant and dreamlike comparison between two different ways of conceiving parenthood (and motherhood, in particular) each of which reflects the society in which it takes place. If Rose’s mother lives her family life in an aseptic way, having to face the duties of a professional and social worker (as also mentioned by the director herself in our interview) that present capitalism requires, Aisha remains anchored to a decidedly warmer and more welcoming conception of being a mother, but also inevitably alienating compared to a world that demands very different rhythms from every woman. Aisha also lives the paradox of having to be a mother to Rose, a little girl who is not hers, separating herself from her son, in the hope to make him live in a better way and giving him a more smiling destiny than his current life.

Nanny carries on a deeply political discourse, in which society is exposed to its contradictions and needs to which we are now accustomed. All this is experienced firsthand by the protagonist, who takes refuge in her dreams to find comfort, even if it is precisely in her dream imagination that the girl receives signals that perhaps something is not going the right way. Alternating sequences of dry realism, with short and direct dialogues almost devoid of musical accompaniment, with moments of dreamlike transfiguration, Nikyatu Jusu presents us with the image of a woman who is both mother and daughter, private and professional, interpreted at a high level by the actress Anna Diop, already seen in Us. In the search for the compromise of all these facets, the film finds its greatest fulfillment, that is, in the representation of the various inner drives to which a young woman is called to respond, adapting to a vision of this problem that is certainly not rosy.

Nanny Review: The Last Words

Cold tones decisively dominate the scene in Nanny to bring the perspective of the facts back to a vision as close as possible to real feeling. The decision to limit the use of music to the bare minimum also goes in the same direction, emphasizing the moments that deal with the story told more abstractly. The poignant and ruthless epilogue then leads us directly to a substantial regression, bringing everything back once again to the dimension of the maternal womb. Nikyatu Jusu demonstrates in her first feature film that she knows how to talk about complex topics and knows how to do justice to the cumbersome stratification that characterizes her main character; it is no coincidence therefore that Nanny was awarded the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in the US drama section and that the director was nominated for the Independent Spirit Award 2023 as one of the most promising directors.