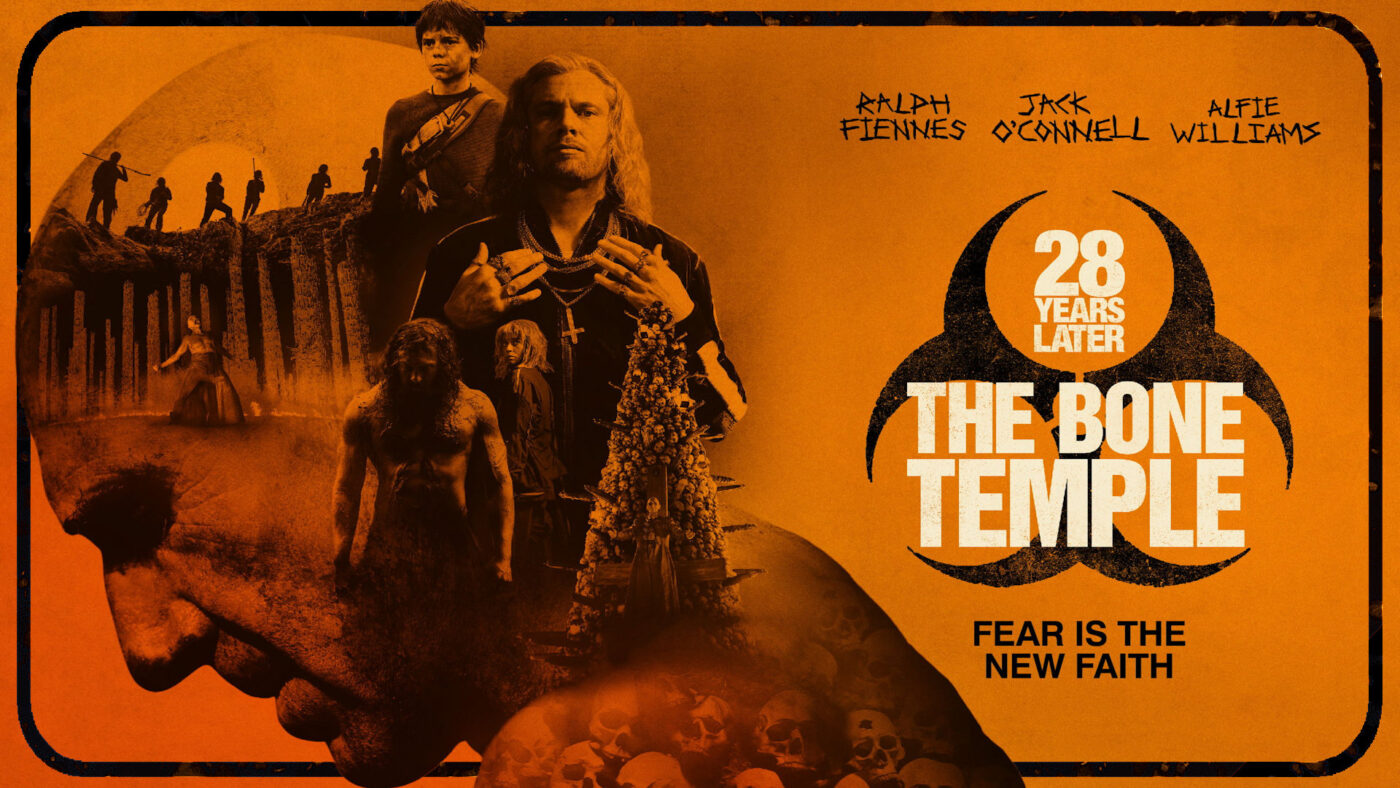

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple Review: Horror and Poetry in a Sequel That Verges on Perfection!

If the good cinematic year is seen from the start of January, 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple It really promises a great year for 2026. The second chapter of the new trilogy that expands the universe born from the film of Danny Boyle It is, without too many turns of phrase, exciting. At this point, it becomes difficult to argue that the horror franchise’s revival isn’t just a commercial calculation, but a project supported by fresh ideas, a coherent imagination, and a willingness to delve deeply into the original story to explore new themes, with a clear commitment and authentic involvement of the authors and performers. The most obvious surprise of this chapter is the radical tonal change compared to its predecessor. The first 28 Years Later had divided precisely by his ability to graft strong emotional transport into a zombie-dominated horror setting: a story of family ties, of parenthood (paternal and maternal) that reached unexpected moments of lyricism.

The Bone Temple is its direct continuation in temporal and geographical key, but chooses a different path: it is more horrifying, more violent, more explicitly splatter, and at the same time crossed by a surprising ironic streak. He doesn’t take himself too seriously, except when it is necessary to do so, and, often, it results in a funny tenderness born of the desire of some characters to protect and help others. The theme of fatherhood does not disappear, but is expressed in deviant forms, sometimes grotesque, but which confirm how crucial it is how we were raised to establish who we could become. Already on the occasion of 28 Years Later, released last year, we were talking about how Danny Boyle returned to one of his most beloved works to fill the void of zombie movies at the cinema. A genre that went pretty strong in the last decade, thanks to and through the fault of The Walking Dead, then gradually faded. Alex Garland remains in the script again, but this time at the helm is American director Nia DaCosta, who will be in theaters from January 15th with a film shot ‘back-to-back’ with her predecessor. That is, made one after the other, a practice used to ensure a certain artistic continuity between the works and, above all, save quite a bit of money if the two films keep the same actors and the same locations, exactly as in this case.

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple Review: The Story Plot

In 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, little Spike (Alfie Williams) returns, recruited at the end of the other film from the small group of “Satanists” of Jimmy Cristal (an excellent Jack O’Connell), sadistic leader of a handful of kids who profess to be the son of the devil in a vinegary suit and oxygenated hair. Also central, however, is the bone temple erected by Dr. Kelson (a great, generous, moving Ralph Fiennes), a memento mori with already iconic geometries, which, rising upwards, detach themselves from the macabre and find the sacred. The relationship with faith, or rather with the fall of faith, is ultimately a bit’ the main theme of the entire film. Of what ill-herbs grow in the meadow of those who do not cultivate memory, and to what chilling distortions the loss of reason leads, of what false idols make their way in such a context, and of what laws these justify by virtue of their own name.

Garland, once again, doesn’t hide behind the zombie metaphor: these films are highly political. And don’t come and say “what balls”. One: because great entertainment cinema is always political and in observation of the present. Two: because in cinema the zombie has always been, precisely, a great narrative metaphor that can be placed in contemporary times (manifestation of consumerism, globalism, conformism). 28 Years Later said that the idea of the presence of the zombie, that is, of the fear that crawls among us (Covid?), in turn pushes towards a form of human regression, the infection of hatred and a primitive isolationism (Brexit?). 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, which then can only be read in diptych with the speech opened by his predecessor, take the reflection a little further’. He returns to the infected and discusses the miracles to which he opens the extension, not without risk, towards the causes and consequences of the infection.

The story continues with Spike (Alfie Williams), who ends up trapped within a violent sect led by Jimmy Crystal (Jack O’Connell). The group functions as a true cult: its members are stripped of all personal identities and called everyone “Jimmy”. According to the rules imposed by the leader, killing anyone they encounter means “freeing them through death, in the name of a higher deity known as the “Goat”. The sect moves like a fanatical and bloodthirsty gang, amidst rituals, sacrifices, and violence justified as sacred acts. Spike is a dissonant element: he doesn’t believe in that creed and fights only to stay alive. To intuit it is Jimmy Ink (Erin Kellyman), a girl in the group who develops empathy for him and begins to question what the sect preaches. When word spreads that the Goat has been spotted in the woods, the group sets out for a place that will eventually become central to the story: The Bone Temple. Here the Dr. Kelson (Ralph Fiennes), a character we already knew in the previous film “28 Years Later”.

A solitary doctor who lives isolated and collects the bodies and bones of the dead to build an ossuary, to restore dignity to the corpses of infected and uninfected people left behind by the post-apocalyptic world. His appearance and the place where he lives are interpreted as supernatural signs, fueling the madness of the cult. A confrontation arises between Kelson and Jimmy Crystal, made of lies, power, and manipulation, which drags everyone towards an increasingly violent escalation. At the same time, the film introduces one of the most interesting elements of the story, the previous meeting between Spike and the Doctor, and a very close and different encounter with Alpha Samson (so called by him), played by (Chi Lewis-Parry). An infected person represents the most extreme and violent form of the virus that takes over the host’s brain and consciousness. An experience that will challenge Kelson in everything he thought he knew about the infected and opens up questions and even, perhaps, hope for the future of the world.

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple Review and Analysis

Crucial to the film is Kelson’s relationship with Samson (Chi Lewis Parry), the huge infected alpha that returns from the previous film. That is, ‘the other’ to reconnect with, seeking him behind the fog of infection and the sleepwalking of reason. Where to praise is the brazen way in which DaCosta and Garland’s work says things clearly and roundly without fear of appearing naive. But indeed, with the audacity to convert the risk of ridicule and menace into a revolutionary act, into a gesture of faith and immense charity moved by a humanist atheist (or, indeed, a doctor) despite his apparent senselessness.

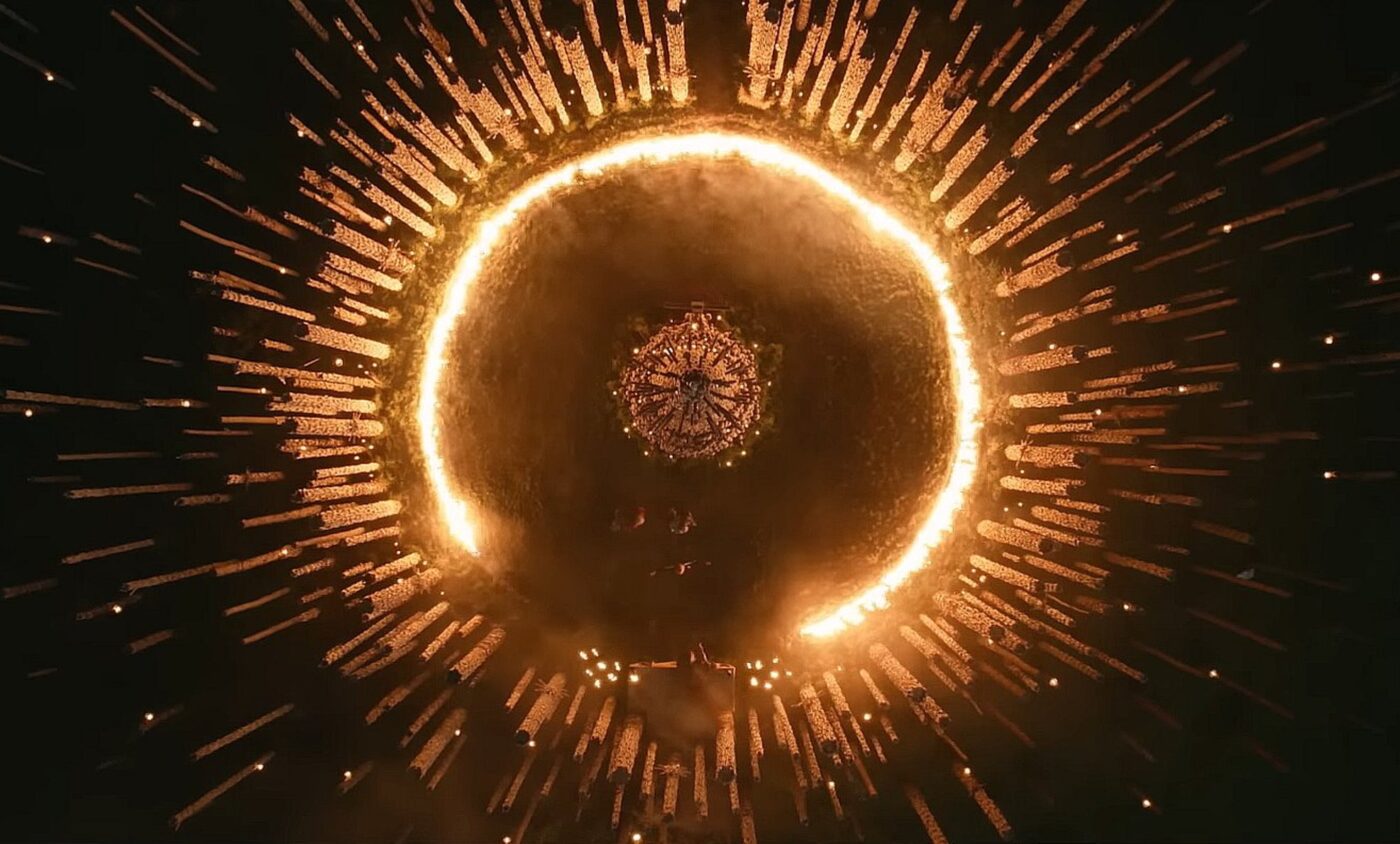

Far from a little in an era as mad as our contemporaneity is, where the concepts of common sense and empathy have been crumbled, where one does not launch into utopia, but one indulges in mowing and bullying. Especially 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple achieves an increasingly rare feat in Hollywood: taking a pre-existing world, continuing to expand its imagination, populating it with powerful characters, and courting philosophy even in the most pyrotechnic sequence, like that of a dance in the flames to the rhythm of Iron Maiden (when you see, you’ll understand).

Because films like this make the leap in quality when the theme is supported by remarkable form work, chock-full of relevant images and moments of impact. With DaCosta, inherited from Boyle, replicating some dizzying camera angles while leaving aside the hyperkinetic hand of the English director, choosing a more contemplative approach without, however, sparing the brutality of a world that is, and remains, consumed by barbarism. At the end, there is a surprise, which is not such a surprise, that with a single blow will bring happiness to those who love the saga and prepare the ground for a sequel, already in development. For once, we can’t wait. The Bone Temple is probably the most disturbing and symbolic chapter in the entire saga. This time, we choose not to focus entirely on action or immediate terror, but to delve into the most uncomfortable fear: that which arises from human beings themselves. The cult led by Jimmy Cristal demonstrates that, in a world without rules, faith can become an even more dangerous tool of control than the virus.

The character of Dr. Kelson is one of the most fascinating in the film. He is not a hero, he is not a savior, but a man who stubbornly tries to remain human. His relationship with the infected, and in particular with Alpha Samson, is one of the film’s strongest ideas, because it suggests that beneath the anger, violence, and contagion, something calling for peace may still exist. It is a fragile and imperfect hope, but for this very reason, profoundly human. One of the aspects that struck me most was Dr. Kelson’s discovery about the possible cure. The film says something disturbing, but very human: even when the virus takes control of the brain, transforming the host into a primitive and ruthless killer, a part of consciousness doesn’t seem to disappear entirely.

It’s as if she’s just standing there, asleep, suffocated, and tortured by constant waves of anger that don’t belong to her. Kelson senses that by quelling that murderous rampage, through morphine and sedative drugs, the virus is not eliminated, but the violence is put to sleep, slowly allowing consciousness to resurface. It is not an immediate cure, but the idea that being infected can return, step by step, to being human and not just a bloodthirsty beast opens a glimmer of hope, perhaps the most powerful and important reflection in the entire film.

In the most memorable passage of the film, a very powerful sequence to the most “satanic” notes of Iron Maiden, Fiennes demonstrates that he can create a character as iconic as his Lord Voldemort, played however on a surprisingly ironic register and, when necessary, of great emotional depth. It’s a huge performance, destined to remain one of the most remembered of 2026. Merit must be given to those who are managing this return: after The Bone Temple, it is clear that 28 Years Later not only does it work, but it evolves. Curiously, the film seems to overturn the approach of Trainspotting (which launched Danny Boyle’s career) by transforming medicine and drugs, reduced to artisanal witchcraft, into tools to cleave the fog of a mind colonized by trauma. The message is surprisingly contemporary: the possibility of cure concerns zombies and humans alike. The ending, in this sense, is emblematic, because find humanity where we would least expect it, suggesting without proclamation an invitation to take care of oneself, of one’s mind, in a world that seems increasingly less stable, devoid of that “unshakable sense of security” that Kelson associates with before the fall of humanity.

Returning, wonderful and poignant, is the unmistakable writing of Alex Garland. The author, always able to condense into his works a large number of painfully current themes, here weaves a story made of madness and reasoning, in which solitude is sometimes a blessing and sometimes a condemnation. The emblematic character of Dr. Kelson, played by Ralph Fiennes incredibly expressive and in great form; it can be considered the fulcrum and synthesis of this new series of films: a pragmatic man, dedicated to the scientific method, but who does not repudiate feelings; rather, he welcomes them by yearning for every shred of humanity left. Almost like a mystical figure, Kelson embodies intellect and compassion, yet, at the same time, is also melancholy at the loss of a world that no longer exists. His, again, is one of the revealing lines of the entire film: when asked what he remembered of the world before, he replies that “The most vivid memory is that there was a sense of security. That sense of security that we still feel on this side of the world, but that, just like in 28 Days Later, is nothing more than a mere illusion, the fruit of a false sense of control.

These are the touches that make Garland’s writing and his characters so profound, authentic, and for some even rejecting: they punctually tell us the unpleasant and failed sides of our society without do-goodism, but with the raw power of a merciless, surgical yet, in some ways, poetic analysis. We come now to the direction by Nia Da Costa, one of the elements that, by necessity, determines the success of the feature film. As mentioned, the fear that the change of hands could create discontinuity proved futile: the director managed to put herself at the service of the saga’s aesthetics while maintaining her stylistic signature. Although not as copiously present as in the previous film (mostly shot on an iPhone), the livelier sequences make good use of action cameras and handheld cameras. However, what certainly strikes the viewer in the heart are the many powerful images and evocative that boast an impeccable composition, where it is possible to fully appreciate Da Costa’s style. A special mention goes finally to the choice of music: a heterogeneous and well-studied compilation that brings together Radiohead, Duran Duran, and Iron Maiden with surprising consistency.

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple Review: The Last Words

28 Years Later – The Bone Temple arrives in theaters and fears of a change in direction from the previous installment have proven unfounded: Nia Da Costa crafts a visually powerful work that respects the frenetic aesthetic of the franchise by adding a poetic and impactful composition. The film is fully convincing thanks to Alex Garland’s deep and witty writing and Ralph Fiennes’ masterful performance, capable of embodying the loneliness and melancholy of a lost world. A highly promoted sequel enhanced by an eclectic and coherent soundtrack. 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple is a film that dares, sometimes hits the mark, and other times stumbles. It works when he tries to say something more about fanaticism, and what remains of the human, even after the virus, especially thanks to a strong character like Dr. Kelson and disturbing scenes that leave their mark. At the same time, however, it suffers from a first part that is a little too slow and some off-key moments, in which the irony clashes with the gloom of the saga. It is an imperfect but interesting chapter, one that divides, but which has the merit of not simply repeating what we have already seen.

Cast: Jack O’Connell, Ralph Fiennes, Emma Laird, Alfie Williams, Chi Lewis-Parry, Robert Rhodes, Maura Bird, Sam Locke, Ghazi Al Ruffai

Director: Nia DaCosta

Filmyhype.com Ratings: 4.5/5 (four and a half stars)

One Comment